I usually love reading musicians’ words on their own music. Both illuminating and opaque reflections are fun and telling in their own ways. My liner notes to Connectedness lean more opaque, at least with respect to technical musical details, since my audience (hopefully) contains non-technical but open-minded listeners who take in music for its emotional and aesthetic properties rather than its nuts and bolts. But of course, there are those like myself who also hunger for the secrets up the magician’s sleeve, as it were. What follows is for you guys.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

An overarching and also permeating principle of the album is duality: the two-ness of opposites that are also the same. The concept of duality’s home in mathematics but is, of course, right at home in music. Major vs. minor, tritone substitutions, notes vs. rests, … So much music is about maximizing contrast but also interrelationship, and any process or concept that generates new music from old is eagerly welcomed into the musician’s bag o’ tricks. In the case of Connectedness, the tracks were composed in dual pairs, symmetrically arranged around the center track, “Reflected off the Water” (which is indeed self-dual). The introduction, “Opening Up,” is outside of this structure. Specifically, “Ordinary” and “Long Line” make a pair, then “Boiling” and “A Crack in the Ice,” then “Zenith” and “Nadir,” then “Indigo Conjunction” and “Viridian Forest & the Night Sky.” There’s nothing particularly fancy going on here; the duality was more of a general principle in the back of my mind as I composed, not a specific procedure. I bring it up so that it makes sense when I break down the tracks in pairs (except for the two un-paired ones).

0. “Opening Up”

Sonny Rollins is my god; Way Out West, The Bridge, and Alfie were strongly in mind when I worked on Connectedness. One of Sonny’s amazing tricks is to pit bluesy/modal/folkloric playing against rigorous, elevated bebop, a sort of call-and-response between two modules within his own musical personality. On Way Out West in particular, his blues playing takes on a cowboyish hue. I wanted to lift some of that for several reasons: my own “western” (Californian) origin, as an affirmation of the validity and depth of American folk culture, a nod to Robert Stillman’s Horses as well as Way Out West. But instead of bebop, of which I am obviously not a Sonny-level master, Middle Eastern melodic improvisation/composition comprises the other pole in my juxtaposition. (“Middle Eastern” is an extremely broad category; I am most familiar with Armenian, Persian, and Turkish styles/ideas, and I freely draw from these without over-sweating “authenticity” or consistency. Bulgaria and Albania, more Balkan than Middle Eastern but not without overlap, will end up creeping in later on, too.)

The outline of “Opening Up” is:

An antecedent blues-cowboy melodic phrase that alternates between adjacent notes in the D minor pentatonic scales as it weaves downward from the top of the saxophone range to the middle, punctuated by two fat (subdominant-implying) rhythm section hits.

The consequent to the previous phrase, which works its way to middle D; the rhythm section punctates again and confirms D minor.

A dualized repetition of the first two phrases — D minor is transformed into D♭ major and subsequently D♭ minor. (Neo-Riemannian theory characterizes this move as an L-P-R transformation followed by just P — whatever, dude.) Very few listeners would identify the slippery half-step modulation as important, but one cool thing about idiosyncratic instruments like the saxophone is that nearby key areas can take on strikingly different colors because of the unevenness of the instrument and the technique it requires — that’s what I’m going for: pitting an “easy” key against a “hard” one.

After the 2+2 cowboy phrases, I present another version of a descending modal pattern that highlights adjacent notes. The descending “up-down-up-down” flourish is ubiquitous in Middle Eastern music and it’s part of my melodic repertoire. First I do it in A lydian (a cousin of D♭ = C♯ minor), then passing through F major/D minor (recalling the top).

The third primary color of “Opening Up” is rubato free jazz. The end of the Middle Eastern pattern twists from A over D to A♭ over C: an implied tritone relationship, another instance of duality. The washy, bubbling moment where the band comes in for real on the A♭ dominant chord is, to me, like color flooding into a previously black-and-white scene. The band nurtures the roiling texture and acclimates us to some bona-fide jazz harmony, preparing the final thrust.

The last phrase sequences a nearly-even melodic shape through quick, chromatic harmonies (more tritone games). The arpeggio contorts a little bit in order to grab the harmonic footholds the chords allow — this is one of my favorite harmonic effects, and indeed a very old one.

The final two chords serve three purposes: 1) recall the descending minor-third rhythm section statement from the very beginning; 2) exploit the near-symmetry of the dominant chord that smoothly connects it to minor-third neighbors; and 3) set up the F major center of the following track, “Ordinary.”

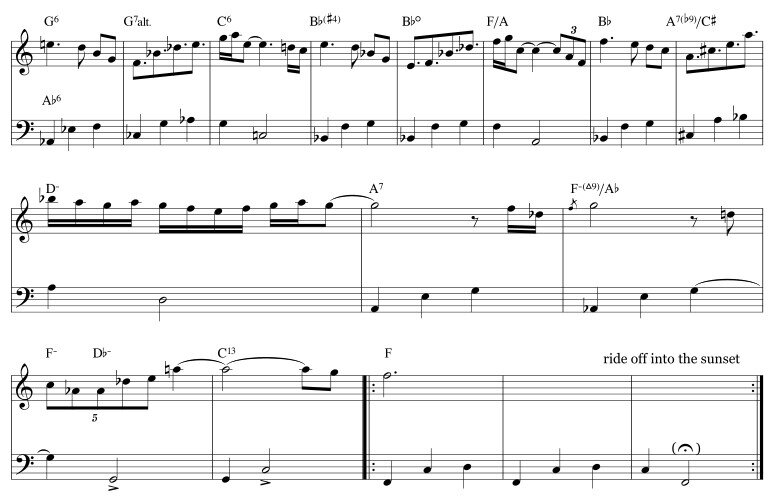

1. “Ordinary” and 9. “Long Line”

The exciting gambit of “Opening Up” is a bit of a fake-out; the album “truly” begins with a simple, calm, mysterious song. Likewise, the finale, “Long Line,” is more of a ride-into-the-sunset moment than a bombastic “and the curtain falls!” one. They share the same basic setup, too: an active, through-composed bassline underneath an operatic melody, bathed in a cowboy atmosphere. The second halves of both songs are basically the first halves transposed by tritones, and each composition finishes with an on-the-nose 1-over-I preceded by one of the two strongest tonal cadences: iv-I in the case of “Ordinary;” V7-I in the case of “Long Line.” (The voice leadings of those two moves are essentially the same; they are indeed dual.)

“Ordinary” is more tender and diatonic, the only tricky harmonic move being the slide from F major to B major, negotiated by a D♯ half-diminished chord in 3rd inversion.

The rest of the harmony is by-the-book: a good-ol’ American dollop of subdominant, particularly as the non-standard downwards resolution to V7/V, and the welcoming of the sixth scale degree as a happy member of the tonic major chord. The outro G♯ minor vamp is a nod to the title track of Robert Stillman’s Horses, whose Americana-inflected opening track, “The Dance 1,” is part of the DNA of “Ordinary” as well.

* * *

“Long Line” is more adventurous. The placid opening bassline is indeed stolen from Majora’s Mask, but it starts to morph as soon as the melody enters. The first chord progression (supporting the initial 10-bar melodic phrase) is more or less taken from a Bulgarian musical, but truncated so that C#7 returns to D major rather than the B-major-to-B-minor-to-F♯-minor cadence in the musical.

I love this chord progression and it appears elsewhere on the album as well as later on “Long Line” albeit transposed). The second chord progression, supporting the second, snakier melodic phrase, functions as a connector between D major and B major. (“Long Line” interpolates D and A♭ between the F-B poles; it spends time in all four key areas while “Ordinary” employs just two. The basic outline of “Long Line” is: 1) D major intro/melody; 2) B major solo section; 3) A♭ major melody; 4) F major outro.) The solo section is basically centered on B, with two quick trips to D major and G# dominant. My favorite part of the section is the cowboy counterpoint at the end; on the subject of “obscure Zelda melodies I stole,” yes, the bass plays “Sheik’s Theme” from Ocarina of Time starting in m. 66.

Taken together, “Ordinary” and “Long Line” moreover highlight the (somewhat subtle) difference between 6/8 and 3/4 time signatures, the double- vs. triple-meter duality present in so much music. While “Ordinary” cleanly separates the dotted- vs. non-dotted-note streams into melody and bass (leaving drums to glue them together), “Long Line” features a melody that flirts with both subdivisions as it floats over the repetitive 3-bar bass shape.

The “cowboy bookends” of the album surround the “real” jazz; “Ordinary” allows the listener to settle into the sounds of the instruments via an unchallenging melody; “Long Line” caps the journey with an unhurried operatic flourish and the final sparkly embers of the album’s harmonic world.

2. “Boiling” and 8. “A Crack in the Ice”

“Boiling” was actually the first completed composition of the album, and was in fact probably what gave rise to the project in the first place. On November 10, 2016, Simón, Avery, and I played as a trio for the first time, and I brought in my then-brand-new tune, untitled but with the descriptor “boiling” for the opening out-of-time section. Long story short, the band just worked, Simón told me “that’s the title, man,” and the second we finished playing, I bolted for a piano to write more. “A Crack in the Ice” came later, after I had settled on the duality theme. So in some sense, “Boiling” is the original material and “A Crack in the Ice” is a purposefully contrasting response. These two are far less obviously connected than the cowboy pair. “Boiling” is all about improvisation and interaction, alternating between aggressive out-of-time jazz and aggressive in-time jazz, while “A Crack in the Ice” is rather tightly constrained and cloaked in a cold, foggy demeanor. I suppose in this pair I am leaning towards the oppositional qualities of duality, de-emphasizing the samenesses.

“Boiling” begins with one of my favorite “jazz games:” out-of-time group improvisation trying to hit chord changes together. It’s somewhere between Simon Says and Chicken, game-wise, and you get these blurry harmonic edges that are impossible to compose directly. The first chunk, leading up to the in-time melody, once again exploits tritone symmetry and two different shadings of the dominant chord; I personally listen for the subtle chromatic inner voice leadings rather than “the chords themselves,” lest I find myself flipping the tritone coin with F and B in my ears.

The subsequent “A” section, where the real melody begins, takes a circuitous path to B major, the loose home key for all of “Boiling.” (B is honestly just such a great key. The comfiest key on the piano, fun and “grippy” on tenor with all the side keys, and the bass’ open E string makes for such a warm subdominant, even more pleasing than open-E-as-tonic.) There’s some sneaky harmony in the form, but nothing too special — relatively straightforward jazz fare — even a couple ii-V-Is!

Melodically, “Boiling” is essentially built of three pieces: 1) the pattern of 4 descending notes then an ascent that begins the whole track, kicks off the melody, and comes back several times within it; 2) the up-down-up-down Middle Eastern scale pattern that first appeared in “Opening Up,” placed in a double-time swing context; and 3) the whole-tone bassline that will re-occur throughout the album and be dualized itself:

The central metaphor of “Boiling” is best embodied by the transition at the end of form, where the time breaks down (“boils over”) and we move into out-of-time improvisation à la the intro. Anyone who cooks knows the moment: the pot is suddenly bubbling up like crazy, and you rush to run down the fire, hopefully saving yourself from a big mess or worse. In this jazz context, the in-between moments are the most exciting to me: feigning an ametrical melodic twist before the rhythm section really gives up the pulse, or bending a rubato phrase into the freshly reestablished tempo. All in all, it’s jazz with a bit of an edge. On our particular recording, I’m especially proud of Hayoung’s Herbie-esque solo. It’s just perfectly constructed and so swinging.

* * *

“A Crack in the Ice” dispenses with the extroversion and bubbly loquaciousness, generating tension through mystery instead of loudness. The opening melody, harmonized in elevenths (a trick I lifted from “Paula’s Theme” from Earthbound, itself a rearrangement of “Youngtown” from Mother), appears elsewhere on the album, most obviously on “Viridian Forest & the Night Sky,” but this is its most complete, straightforward presentation. One interesting thing about jazz harmony is that because chords often have many notes, it is possible to voice thirds-based chords in fourths; in fact, using ninths and thirteenths to “quartize” the sound of, say, a tonal seventh chord, is a classic recipe to make your functional harmony sound like jazz (or French Impressionism). The move from “Boiling” to “A Crack in the Ice” abstractly represents this thirds-to-fourths shift. The second harmonization of the melody in “A Crack in the Ice” tempts the listener to recover a tonal context from the neutral gray fourth-chords.

“It’s like G minor, but it smells weird!”

The final harmonization of this melody, near the end of the track, is even more melty and diabolical. Imagine repeatedly strumming three guitar strings tuned a fourth apart but also constantly detuning them so that the composite chord squirms ever-downward. “Boiling” has a couple of analogous squirms, but they are all tempered by good ol’ tonality and hence are less infernal.

A more direct thematic connection comes at the sudden shift from in-time to out-of-time. The descending figure that initiates “Boiling” is flipped upside down and sequenced from the bottom of the saxophone’s range to the top. We play another rhythmic game: start and end a long phrase with (almost) the same number of notes together, but don’t line up along the way. The Intermediate Value Theorem guarantees that our emergent tempi pass through each other.

The brief solo-piano moment before the bass improvisation has a similar (“Boiling”-related) motivic idea under the surface, made even more symmetrical and obvious (this one’s for you, Béla).

The last major piece of “A Crack in the Ice” is the slow rubato melodic passages with tenor way up high and bass pedaling an open string and a thumb-position melody (parallel with tenor) simultaneously, arco. The sonic effect is cold and foggy, the piano and brushes accompaniment acting as little ice crystals, small bits of hard texture floating in a vapory mass. The melody appears four times, and each time Simón pedals a different opening string: four different shades of dark blue-gray.

Lastly, I will mention the modal trick behind the bass solo and the outro of “A Crack in the Ice.” The instructions on the page say “Locrian/Lydian” over the same bass note. Locrian and lydian are the two modal extremes of the diatonic scale, and at first glance may seem to be as different as can be. For instance, E locrian comes from the F diatonic scale while E lydian comes from B (raise your glass to the mighty tritone once more). But what may appear as opposites can often be reinterpreted as dual partners: stacking ascending fourths on E produces the E locrian scale, while descending fourths (or dually, ascending fifths) creates lydian. None of the other modes have this property of “maximum quarticity/quinticity.” Another beautiful game you can play is to transit through the modes over a single root note. So, for instance, C lydian — C ionian — C mixolydian — C dorian — C aeolian — C phrygian — C locrian. Each move only requires one note in the scale to move down by one half step. It would seem at first that the game must finish at locrian, but if you “de-privilege” the note C, you can continue the pattern indefinitely by gluing B lydian to C locrian, which are indeed just a single half-step shift away from each other. Then, the cycle loops back on itself after 84 moves, hitting all seven modes on all twelve notes. A consequence of this that I use in “A Crack in the Ice” is that any locrian voicing can be transposed up a half step to become a lydian voicing over the same bass. Try it!

“Boiling” and “A Crack in the Ice” both play with in- versus out-of-time sections, exploit harmonic symmetries, and share motivic material. On the other hand, they represent the opposing extremes of “temperature” on the album and are paced very differently than each other.

3. “Zenith” and 7. “Nadir”

Moving inward, we arrive on the two “episodic” tracks, each of which juxtaposes two totally different musical characters and jumps back and forth between between them. Both tracks have a dark, spidery character; “Zenith” compares this to a light, bouncy groove, while “Nadir” pits it against hard rock.

The musical machine that sets “Zenith” in motion has three layers: 1) free-time drums playing almost-triplets accelerating and decelerating like a gentle breeze; 2) bass + piano freely but slowly arpeggiating triads; and 3) a saxophone melody that weaves downward in huge leaps — imagine the big, slow, careful steps you’d take from foothold to foothold descending a mountain. The melody itself purposefully steps around chord tones, only coming to rest when it has to land on the shifting harmonic platforms. The supporting triads move by major third (mostly): E major — C major — A♭ major — C minor — A♭ major — A♭ minor (= G♯ minor) — E major. There are few extra chords in there to disguise the naked symmetries and to keep it from being a total neo-Riemannian wet dream, but the major-third-related poles comprise the main structure. Compare to the tritone/minor-third symmetries of “Ordinary”/”Long Line,” as well as the upcoming harmonic symmetries within “Zenith” and of “Nadir.” The out-of-time-yet-accelerating transition to the first solid tempo of “Zenith” indeed relates triads (and one seventh chord) by minor thirds (note that triads are always more smoothly connected by major thirds, while four-note-chords are always more smoothly connected by minor thirds). The C♯ — E — G — E twist is a bit more jagged to my ears than the initial E — C — A♭ one.

In any case, saxophone, bass, and piano come down to a whisper while the drums crescendo, setting up a new 5/4 triple meter. A delicate 11-bar interlude, a moment of alignment, juggles pretty much all of the harmonic considerations seen so far and also plays the triple-vs.-duple rhythmic game.

The reverie ends quickly enough — a couple of long saxophone scales and a cadential fake-out bring us back to the out of time “mountain-descent” melody supported by major-third-related triads, this time with a bit more volume and edge. The first complete arc of the composition comes to a close on a restful E major moment, as if the tune so far had never happened or was just a dream. But then the drums once again push into 5/4 triple meter for the solo section. The first half of the solo form is a gentle and conservative tonal elaboration of E major. The second half is the Bulgarian chord progression (this is its first complete appearance), complete with the (missing in “Long Line”) IV-iv-i cadence in F♯. The tempo disintegrates in the final bars of the saxophone solo, leading to an important piece of thematic material that has popped its head out earlier but fully reveals its true form here for the first time:

This four-note “down-down-up-up” motif is sort of the Beethovenian counterpart of the Middle Eastern “up-down-up-down” figure. It moreover executes a wonderful negotiation between diatonic and chromatic spaces, and also smoothly connects to itself (a major third away) after five cells:

The whole figure, fourteen cells moving through three keys, is essentially the melodic opposite of the beginning of “Zenith”: all fast stepwise motion rather than huge slow leaps; generally ascending rather than descending; nestled in a diatonic scale rather than tiptoeing around one. The line functions as a sendoff to the climax of “Zenith”: one last round of the spidery melody, supported by the major-third-motion and then the minor-third-motion, starting fortissimo but dying to a whisper by the end.

* * *

“Nadir” has a loosely comparable arc but the details are, of course, quite different. The opening machine, this time, is more rhythmically aligned: 1) A 3+3+2 bassline that you might find as the “Cave” theme in a GameBoy game; 2) drums playing a repeating 3/16 figure (cf. the almost-triplets of the introduction to “Zenith”) that goes over the bar lines, sometimes lining up with bass, sometimes opposing it. The spidery rubato saxophone melody offers another level of “misalignment,” floating over the beat, almost lining up at times but not strengthening the meter at all. While the ionian mode has more or less conquered major-key music, (Western) minor-key music is still amenable to variation in modal shading, and consequently, it is easier in minor to draw inspiration from the highly sophisticated modal systems of e.g. Persian and Turkish musics. I fully admit that I am not at all using a particular dastgah or makam anywhere on this track, but I am thinking about how various pitches/intervals sit on and resonate with the open canvas of a minor triad. The first section of the “Nadir” melody is G dorian or D aeolian depending on if you privilege the bottom bass note or the whole triad the bass outlines. (For what it’s worth, I can hear it both ways, a bit like the “rabbit-duck” optical illusion.) The only deviation from G dorian/D aeolian is the E♭ upper neighbor to D in the transitional phrase that links the G minor bass triad to the B minor bass triad. In the “B zone,” the modality of the melody expands: both raised an natural sevenths appear; raised, natural, and lowered fourths appear; there are likewise two different seconds and fifths. I also sneak in a couple of microtones to further juice up the modality.

The modal ambiguities of the B minor section create tension, and in the aftermath of the saxophone melody, drums crescendo while the bass line slips through a neutral quarter-tonal triad to B♭ major, preparing an unadorned V-I to E♭ while Avery shamelessly plays the Phil Collins fill and Hayoung explodes forth with a fast arpeggio, straight from the Beethoven playbook. Woo!

(Not my most subtle music.)

No fake-out here — it is time to rock. I have lots to say about the relationship between jazz and rock — when it works, when it doesn’t, how it works — but suffice it to say for this post that I’m throwing my hat into the ring as such. One outstanding issue is jazz’s appetite for lush (usually functional) harmony versus rock’s retrofunctional norms (rock harmony often moves the “other way” on the circle of fifths compared to classical/jazz; for example, the rock progression I-♭VII-IV-I mirrors I-ii-V-I) and its general avoidance of thickly-voiced chords. My compromise in “Nadir” is to rely on a strong descending bassline that only slightly “nerdifies” I-♭VII-IV, and to change keys quickly to satisfy modernistic/jazz cravings. Mm. 30-31 I more or less stole from the fourth movement of Mahler’s 9th symphony; it is a chromatic alteration of the “Pachelbel scheme” that fits in perfectly with the triads-related-by-major-thirds theme present in both “Nadir” and “Zenith.”

In any case, the rock section only lasts long enough for the listener to not realize I’m huffing and puffing on an acoustic wind instrument and that the band is extraordinarily over-educated for the music it’s producing. The “turn” motif I brought up in “Zenith, which is also rather Mahlerian (see the aforementioned movement), reappears as the time disintegrates and our free jazz “mode” re-engages. The two triads of the opening come back as tremolos underneath a rough-and-tumble saxophone line, capping the aggression set alight by the flames of Collins and Beethoven. A quarter-tone interpolated between B and A♯ recalls the earlier modal antics, preparing the solo section.

The first chapter of the solo section is an expansion of the opening “GameBoy cave level” feel: brooding and not-quite-symmetrical, receptive to expressive modal shadings. The major-third wheel is completed via the addition of an E♭ minor area. After 8 segments, we move on (via Collins again, of course) to an expansion of the rock section: the second chapter of the solo section. This time, the minor-third wheel is closed by continuing the pattern through A and F♯, so that the harmony seems to always descend on average but, as harmony does, ends up right back where it started. After a couple of loops, we get out of the solo by reprising the Mahler transition and the free jazz segment. What follows is an acquiescence of the original bassline to the demands of tonal resolution: a perhaps-slightly-ironic iv-i in G♯, diminuendoing towards a fake “dot-dot-dot” ending. But, “Nadir” being the climax of the whole album, we rock once more and for all. A totally barbaric whole-tone bassline (as opposed to e.g. “Boiling”’s rather pretty one) walks us down an up-escalator, and we freak out until the admittedly somewhat nerdy ending. But if my listeners can tolerate some rock, they can tolerate some prog rock too.

In summary, “Zenith” and “Nadir” both juxtapose episodes of totally divergent music. The lightness of “Zenith,” its musical representation of altitude, comes from the cautious, rappelling melody over a breezy base, plus the effervescent 5/4 triplet groove, more diaphanous than sturdy. On the other hand, “Nadir” skews dark and heavy: a cavernous, eerie melody over a gravelly pair of linked ostinati, plus a hard rock avalanche — the climax of the album. In my mind when composing both was the complex exchange between harmony and modality, or stated as a puzzle, how to get more pitches to “work.”

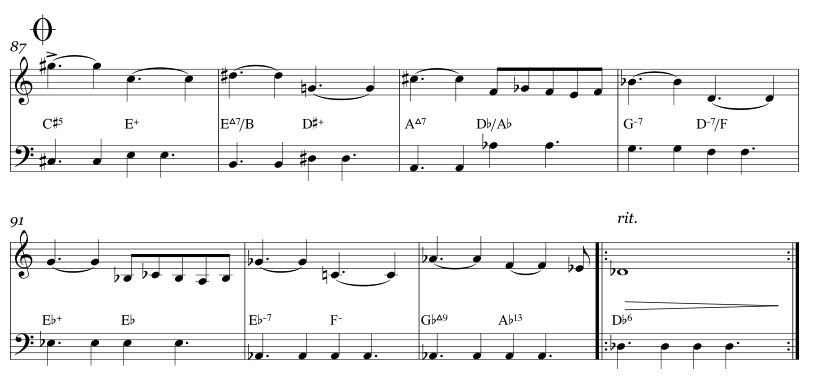

4. “Indigo Conjunction” and 6. “Viridian Forest & the Night Sky”

Having now rehearsed, played, and recorded this music a few years after its initial compositional period, I admit that my ears no longer signal a strong dualistic link between these two tracks. Both of them morphed a bit over time as well, blurring some of of the conceptual linkage. In any case, some shared DNA survived: both feature pedal points, tritone-based harmonic relationship, divisions of beats into 5, and high-energy solo sections. The narrative inspiration comes from an iconic moment that many gamers my age remember: in the first generation Pokémon games, Viridian Forest is the first little dungeon the player reaches, connecting Viridian City and Pewter City. The forest itself is notable for is winding structure and its blunt, almost abrasive tritone-based theme, but the area it leads from, Viridian City, is interesting because it serves as both an introductory area just after the player’s hometown, Pallet Town, but also the site of the final gym and the lead-up to Victory Road and Indigo Plateau, the climactic section of the whole game. That is to say, the whole game loops back in on itself, and fun childhood “wow” moment inevitably pops up when you realize that you walked right past the biggest, baddest enemies mere minutes into your adventure. As a kid, I imagined Viridian Forest as a long, circuitous hallway of grass flanked by tall columns of trees, and it always seemed to be night time there; to this day I can emulate my young imagination tilting my head back and looking up at the stars, the long trunks and leaves in the corner of my view, receding into the distance. This image, plus the astronomical thematics of “Zenith” and “Nadir,” conjured the image of the stars aligning before the climactic moments on Indigo Plateau — as epic in my memory today as they were in ca. 1998.

As for the music! Though “Indigo Conjunction” and “Viridian Forest & the Night Sky” form a dualistic pair in the larger context of the album, they serve secondary functions relative to other tracks. “Indigo” bears resemblance to “Boiling” — energetic, swinging, jazz harmony — and “Zenith” — 5/4 swing and the descending-leaps melodic idea — so that the first half of the album is the “jazz half”: a bit more approachable (at least to a jazz-steeped listener), less abstract, faster-paced. On the other side, “Viridian”’s darker tone and episodic form, as well as some of its specific motifs, connect it to “Nadir” and “A Crack in the Ice,” fleshing out the “non-jazz (or ‘less jazz’) half,” where rock, opera, and videogame music push back on the jazz aesthetic.

The 5/4 in “Zenith” is light and bouncy; the upcoming 5/4 in “Viridian Forest & the Night Sky” is plodding and heavy; the 5/4 in “Indigo Conjunction” is somewhere between: a repetitive pedal figure but not strictly symmetrical, and the swing tempo admits the duple v. triple game I mentioned before. “Indigo” opens with a short drums improvisation over the pedal then launches into the melody, which was totally freely composed without motivic connections to the other tunes save for the “Zenith” melody shape in the send-off and the coda. The melody line twists and turns without much respect for the barline, and possesses a more improvisational character than some of the other, more straightforward melodies. Perhaps a bit of Tristano peeks through. Harmonically, the scheme is essentially “Inner Urge”: a pungent, evocative half diminished chord to start (in this case, D half diminished in 3rd inversion); a series of lydian chords moving in a strict pattern (up-a-minor-third instead of down-a-whole-step); then a final episode of quick harmonic moves exploiting the symmetries that connect jazz chords.

The above snippet — the end of the melody going into the blowing section — shows off some of the rhythmic tomfoolery and the pretty chord progression that sends off the head. The descending-leaps shape is quite like the opening motif of Bartók’s first quartet, and moreover, the chords supporting this instance of the motif are quite like the chords he uses at one equivalent moment in the first movement of the quartet. The “big harmonic reveal” at the climax of that movement is an arrestingly beautiful voice leading pattern that connects major and minor on A, F♯, E♭, and C — the diminished octagon that probably brought more than a single tear to Ernő Lendvai’s eye — but the same melodic shape is supported with slipperier and somewhat more opaque harmonies earlier in the movement. My version is not-so-symmetrical, closer to the latter option, but still fits very comfortably under the hang if you take a moment to compute good voice leadings.

After the send-off, the solo section echoes the opening, pedaling C. But it is really the beginning of an eight-bar phrase alternating between C and F♯ pedals. (Yes, a harmonic scheme like those in the cowboy tracks is at play.) This anxious vamp admits modal playing more than harmonic; one is free to play octatonic stuff or emphasize major/minor subsets of that big scale. For what it’s worth, this is always a very fun but also dangerous section to blow over: there are many possible modal/harmonic choices, and if Hayoung and I guess clashing options at the same time, we can get into hot water. This is where we test our telepathy and sensitivity (she has insanely good ears and I’m not an aural mega-slouch either). In my opinion, harmonic areas that feed off these kinds of symmetries (see Bartók again) always build tension and creepiness, like infinite mirror hallways or mazes in the woods. That’s the idea here; we charge up energy on the pedal-vamp and then release it in the second chapter of the solo form, where the walking starts. The harmonic scheme here is simple: a four-bar phrase connecting A major to F♯ minor followed by its transposition down a minor third, connecting F♯ major to D♯ minor (the last chord being muddied up as a dominant♯-9, minor’s angry cousin, to launch into the next phrase). The third phrase supports a non-necessarily-played instance of the “Zenith” leaping motif with some more snakey late-romantic harmony, and the fourth phrase slows down the pace of the root movement, re-setting up the pedal section. As you might have learned to expect by now, when the form resets, it is a tritone away from where it started. Both solos are twice through the form, but the first pass begins on C while the second begins on F♯. But because the opening pedal episode alternates between C and F♯ anyway, it’s a bit tricky to find footing here, both as listener and player. That’s the point! Unlike other solo forms on the album, this one, to me, kind of encodes the narrative a soloist ought to take, though hopefully not too strongly. The sections are so distinctive, though, that to approach them all in the same way would be harder than just catching their waves and riding along.

The large-scale form is quite simple: intro; melody; tenor solo on both tritone-halves of the form; piano solo on the same form; piano begins the melody and tenor joins for the second half; coda out. Excuse the immodesty but I am quite proud of the harmony of the coda; I think it’s the most romantic and magical chord progression of the whole album, and it really breathes along with the melody.

The dark, impish character of the pedal points under the rest of the melody is replaced by a warmer, fluffier pedal-point moment in the final measures. I just love the sound of parallel diatonic chords over a bass pedal. I also really like the transition of D♭/A♭ to G minor across the 3rd and 4th measures, though I’m not quite sure why it works so well! If it were not for the G chord, the D♭ chord might be more appropriately spelled as a C♯ chord connecting A major to F♯ minor (the two subdominant(-ish) key areas in C♯ minor, which is probably what I’d call the loosely prevailing key area from the beginning of the coda). But a C♯ chord after an A chord could also reasonably connect to an F♯ major chord (instead of minor) with A♯ in the melody; recontextualizing the A♯ as B♭ but then switching the support back to a minor chord produces G minor. Chalk it up to a little Neo-Riemannian flourish or just accept smoothly-voice-led chromatic movements as inherently valid, or, perhaps better yet, don’t worry about it too much. If it works, it works, and this works to my ears! Plus, who isn’t immediately won over by a warmly-voiced D♭ major ending? It’s the velvetiest of the keys, the luxurious connoisseur’s tonal vacation home.

* * *

Even the tense moments of “Indigo Conjunction” are in relatively upbeat humor; it’s probably the most fun tune overall. “Viridian Forest & the Night Sky” is more or less the opposite — quite tricky to play and rather demanding on listeners who seek out a thread of coherence. That said, the composition is indeed playing with some of the same elements in “Indigo Conjunction,” and the overarching form is relatively straightforward and symmetrical, though more segmented than “Indigo”’s. The opening atmosphere is essentially a one-beat loop: bass drum bumping along underneath quintuplets on brushes. Compared conceptually to “Indigo,” this is about dividing a single beat into 5, rather than a whole measure (which is itself a sort of larger beat). This rhythmic setup, sometimes called “small fives,” is something of a hackneyed modern jazz trope at this point, but if I may offer an explanation as to why my version is better, it is because I did not commit Avery to a fixed sub-subdivision (like 3+2 every time, say). He phrases his accents unpredictably so that the more open and abstract “five-ness” prevails over the perhaps more common 3+2 or 2+3 options, which are certainly constricting. There are 32 distinct ways to accent or un-accent five notes in a row, and if you expand to include three options per note — accented, unaccented, or rest — the number of possibilities shoots up to 243. Which is just to say there is so much variation in phrasing afforded by big subdivisions; it is therefore a shame to stick to just one or two basic patterns. My man Avery knows these numbers and it shows!

Returning to the subject of the texture of the opening, the original version of “Viridian” included a bass pedal with the bass drum, but it was determined to be a bit too heavy and obvious, so the first melodic statement is just a duet of tenor and drums. The tenor melody is very rhythmically basic, but its “natural phrasing” is delayed by an eighth note so that what would have been its downbeat attacks lay in the tiny gap between the third and fourth quintuplets. The effect is intentionally unsettled, tempting the listener to switch over their perceived pulse. (On top of that, Avery, being the nerd king that he is, throws in other subdivisions of the pulse.) The full band snaps into action after three melody statements and a break; the second melody idea enters at [B]: an almost-banal diatonic melody “creepified” by supporting parallel chromatic thirds, the whole-tone bassline from the coda of “Boiling,” and the quintuplet grid churning underneath. (The first two melodic sections indeed comprise the melodic material from “A Crack in the Ice,” if they seem familiar.) The third melodic section, this time expressed by piano, brings the quintuplet grid into the melody in a rather on-the-nose way that nonetheless feels pretty good in the hand. It’s all five-finger ascending scale patterns, moving between segments of B lydian (except for one E-natural) and F lydian (except for one B♭): like corrupted Hanon. Underneath that, bass simply tiptoes down the B lydian scale twice in a row.

The three-segment arc comes to a close with bass and piano fading away so that the tenor + drums duet can initiate another round at [C], this time a tritone away, of course (the B pedal in the bottom staff got replaced, as before, with just bass drum). The second melody idea returns, too, but the “Hanon” section does not; instead, the piano solo section starts over the quintuplet grid plus bass pedalling for real. The changes exploit the same locrian-lydian trick I explained before, so that the resulting diatonic collections keep playing the tritone game but the root stays fixed. The musical challenge here was to not let such an admittedly boring bass figure bog down the energy. Simón deviates, mercifully, and Hayoung and Avery do an excellent job of obscuring the grid without sacrificing too much groove: the result has forward propulsion but also a certain foggy uneasiness. Chapter one of the piano solo sits on the B pedal, alternating locrian and lydian. Chapter two introduces D as an alternative bass note and switches the chord-scale possibilities to G lydian and B♭ lydian (though not at specific times — Hayoung can freely choose when to switch between the macroharmonic areas, which, to be fair, share many notes). Chapter three keeps the same chord-scales but transposes the bass notes (by tritone) to F and A♭, but more crucially “flattens out” the grid into sixteenth-notes. The eventual goal is to reconceive each individual beat (~75 bpm) as a full measure of 4/4 (at ~300 bpm). The rhythm section is setting up the lone episode of blistering swing on the album, but the kraken is not to be released straight away. The piano solo builds in intensity but then diffuses some energy and dovetails into a new section, a new texture with a new perspective on the beat and its subdivisions.

Avery avoids his cymbals, opting instead for a light sprinkling of pure drums; Hayoung floats on the dissipating updraft of momentum from her solo; Simón hops on to a through-composed walking pattern that expressed the new tempo but also reminds us of the old slow pulse. I’m very proud of the texture they cultivate here: it’s very relaxed and open but also breezy and just a little agitated. The imagine in my mind was riding Epona, galloping through Hyrule Field in Twilight Princess, the weird dull-yellow light enveloping Castle Town in the distance, perhaps an eagle drifting through the sky without a strong purpose, the impossible cliffs standing proud and abrupt in defiance of realistic physics and geology. To that end, the upcoming saxophone melody takes its opening shape from one of the main leitmotifs in Twilight Princess. What can I say? I’m true to my roots if nothing else.

The section I’m talking about is essentially four repeats of a twenty-four-and-a-half measure phrase driven by the bass. The first time through, Hayoung offers a patient, wide-open (frankly American) harmonization of the bass line, Simón briskly chugging underneath — no melody. The tenor+piano melody enters on the second repeat; it moves at its own slower pace, tugging on the meter of the bass+drums (I wrote it as floating non-metrical individual noteheads, loosely arranged on the staff).

For the third repeat, the bass transposes up a minor third but the melody stays the same (except for two notes adjusted a half step to avoid a couple of ugly clashes). To my ears, the transposition is not immediately obvious, but the long arcing run (around the 6/4 bar) sounds much more extreme in the higher key. For the final repeat, the melody catches up to the bass, transposing up a minor third too. The section sneakily flows into a transition where the beat expands into 5/4, recalling the earlier quintuplet grid. Tenor foreshadows two melodic coming up in the second half of the album and flashes back to two others from the first half, then launches into the solo section.

The opening section of the tenor solo is two loops through four minor chords with a composed bassline that continues the earlier bass trajectory. The subsequent main chunk loosen’s Simón role and Hayoung momentarily drops out so that she re-enter with gusto for the climax. The harmony of the section is not really important at all but for what it’s worth, it’s basically a Hans Zimmer-esque plain minor triad sequence. We really push, flirting with the high-gear free jazz mode of e.g. “Boiling,” shooting towards a big payoff after a couple hundred measures of gradual build-up. The climax after the solo is the return of the original theme and the recontextualization of full bars of quick 5/4 as individual beats of slow 4/4 — undoing the earlier metrical transformations. Or, almost-undoing; if you’re keeping track, the original tempo was quadrupled (75 → 300 bpm), then the time signature grew from 4/4 to 5/4 but the tempo did not change; so, when we cut the tempo by a factor of five after the solo (300 → 60), we end up 20% slower than the opening. Which is fine, and arguably a bit more epic anyway.

The remainder of the track reprises the original melodic material (a tritone away), but in a more aggressive voice. (The mighty Kevin Sun calls this “The Virgin Sacrifice.” No virgins were harmed in the making of this album.) The final vamp is like that of “A Crack in the Ice” — the lydian/locrian game over a tritone pedal.

Despite its length and many sections, “Viridian Forest & the Night Sky” is pretty straightforward as an arc, and looking back, it’s almost in a kind of sonata form: an initial section with a primary and secondary theme group; a long, sequential, tension-building development, then a return to the original material with a little extra gravity. One of the oldest tricks in the book!

5. “Reflected off the Water”

Finally, we have reached the cornerstone track of the album, the self-dual central jewel. The two surrounding tracks I just discussed are both rather sophisticated in their own ways; to counterbalance the demand on the listener I wanted this middle track to be simple, beautiful, approachable. My model was therefore “Love Theme” from Robert Stillman’s Horses: an unhurried rubato melody bathed in a warm, heavenly light that glues the album together. I knew moreover that the central track would not have a dualistic complement elsewhere on the album, so the overall form was easy to come up with: two earnest statements of the melody, a tritone apart, separated by a fulcrum moment where time essentially stops and the trajectory of the rest of the album realigns in a new direction. Simple enough in theory, but it is not a trivial task to write slow, simple music without any irony or flashy tricks. And to imbue that natural character — to make it feel like the melody “already exists” — is even harder. To me, it amounts to fully trusting the basics of the systems of music, to faithfully submit to elemental ingredients: diatonic triads, V-I progressions, quarter notes, four-bar phrases, … Hipness and irony corrupts the holiness of those elements, but on the other hand, composing something that’s too basic is itself an ironic, degenerate act. It’s an exercise in balance, where every note takes up space and the total amount of space is very finite.

So how did I fare? Well, it’s not for me to decide, but here was my strategy:

AABA form — tried and true. The A sections feature a repetitive bassline that is a bit like the whole-tone bassline from earlier, but smoothed out into a diatonic mold. The harmonic implication of the bassline is bland: A♭ for six bars, then an F minor scale that lazily connects back to the top, taking two beats longer than it should to switch directions and set up a (rather nonchalant) V-I. On top of the bassline sits the melody: even slower and completely diatonic except for a single E-natural connecting the sixth and fifth scale degrees of A♭. (On some repeats, I omit the E-natural; on others I bend it by about a quarter tone to segment the F-to-E♭ gulf) The top line is ionian with a downbeat-accented major seventh in measure 3, but the bassline features G♭s so that it comes across as more mixolydian until the F minor scale, which is aeolian, featuring a G-natural. That modal mismatch creates a little bit of rub, but it’s pretty subtle because the two versions of G are never simultaneous. Hayoung’s job is particularly tough because any chord could be an imposition on the simplicity of the counterpoint, but she also has the opportunity to add a third stream into the mix, so she ought not be too shy. The rhythms on the page are beyond basic, readable by a day-one music student. We added some variation by playing a game, led by Simón. On paper, he’s just playing quarter notes, but he is allowed to freely (but smoothly) vary his tempo, so that the pulse breathes, mirroring (or contradicting) its melodic momentum. The rest of us play a guessing game, trying to be as perfectly in unison with him as we can despite his outward unpredictability. The result is a sort of Brownian motion of tempo, a tidal cycle of rushing and dragging, and a chance for us to flex whatever telepathy we’ve developed from playing together and being friends.

Simón generally pushes and pulls on the tempo more and more as the tune proceeds, and especially during the bridge, which sequences a hyper-simple IV-V-I progression through the home key of A♭ then C♭ major, a minor third up. The minor third tonicization is peeled off when a scalar descent that sounds like it should begin on C♭ and end in F♭ lands instead on F-natural minor, at which point the scalar descent is reversed; Simón painstakingly and diatonically climbs from his lowest F up two octaves, then turns the other direction to reset the [A] section back in the home key. The end of the last [A] section is similarly extended by a scale; after the six bars of A♭, Simón climbs stewise down the F minor scale back to that bottom F as the rest of the band fades to a whisper.

So concludes the melody and moreover the first half of the album. We experimented with the following moment, the exact center of the whole record. It was always going to be some kind of improvisation — we tried a full-band version, a trio version where I get out of the way for once, but the choice was essentially made for me when, in a single take, Hayoung improvised an interlude that ended up being what got printed. It was just so arrestingly beautiful, so crystalline, so absolute. The heart rate of the music slows to hibernation so that the collective organism we comprise fades out of the picture, revealing a lush yet meek ambient backdrop — a partial memory of a melody; a hopeful daydream; a moment of burbling water transfixing a once-hyperactive child.

Words do no justice to such an uncorrupted moment of inspiration, so they end here. The second half of “Reflected off the Water” is essentially identical to the first. The new key imbues saxophone and bass especially with a new registral timbre, and we play the Brownian motion game slightly differently on the way out. But that’s it — the composition is identical except for a tritone transposition. (On that note, Hayoung’s interlude is even more impressive in how she connects A♭ major and D major. A continuous, casual stroll through the circle of fifths gives the feeling of waking up from a nap on a train, consciousness seeping in as you realize you’ve reached your destination without being aware of the details of the journey.) The four tonicized key areas of the whole track are, in order of appearance, A♭, C♭/B, D, and F, the same square as in “Long Line,” the other semi-operatic track.

In terms of album sequence, I view the first half of “Reflected off the Water” as a moment of respite, like a save point in e.g. Final Fantasy, after the heated energy that builds up through the first half of the album. The second half of “Reflected,” then, is a well-wishing departure, a pushing-off towards the darker, more abstract second half, which is best approached with a recently-cleaned palate. In 2021, where TikTok and other ADHD-paced media dominates, it’s quite a big ask to have listeners sit through an album of instrumental music. My hope is that “Reflected off the Water” segments the experience somewhat, without cleaving it into disconnected chunks. For what it’s worth, it is often these “and now a break from the action” moments that stick in my mind in long musical works (especially operas). The humming chorus in Madame Butterfly; the waltz sequence in Der Rosenkavalier; Ornette Coleman playing “Embraceable You” on This Is Our Music. It’s a delicate balance in music between consistency/continuity on one hand and variation/development on the other. I really value long continuous experiences that draw you in deeper and deeper, but a well-placed, perhaps shocking discontinuity is sometimes just what the doctor ordered! Music, being infinitely deep and sacred, admits no magic formula other than the musician’s own personality.

~ ~ ~ ~ ~

If, by some perverse miracle, you’ve read this whole post and have more questions or want to see more sheet music, please do reach out. I am happy to send complete scores. (Moreover, if you’ve read all this, I think you’re entitled to a free copy of the album — send me an email and I’ll send back the files.) If any of my musical techniques or ideas appeal to you, take them! Counterbalancing the joyful and fun process of generating music is the somewhat painful process of excluding ideas from a project; the pain is abated by the faith that someone else somewhere else will draw from the same source or elaborate on a similar idea. Almost any musical idea is a portal into a deep, unending well of expression. The worst thing that can happen to music is when it’s never played/heard at all — take that as a command to play, hear, and explore!