We all have our vices. Some drink and some smoke. My disagreeable soul, destined for the academy but shut out by fate, cannot resist, from time to time, subjecting YouTube comment-sections to comment-violence. I cannot help it that I have never been wrong on matters of music theory!

The simpletons who dare cross my path surely find themselves enlightened once I sheathe my tongue but nonetheless I know, deep down, that this is all a waste of time. Learning on YouTube is like eating at Yankee Stadium. There is a whole insidious industry of YouTube entertainment that seduces you by wrapping itself in a veil of education. But that's for another diatribe.

Temptation reared its ugly head last week. I had just accidentally fired myself from a company I owned and not one, but two midwits excreted YouTube videos purporting to lay out the meaning of the so-called Tristan chord once and for all. I couldn't not. I am sorry. I will be more Godly next time.

OK but even though I stooped so low as to roll in the mud in the educational wasteland of YouTube, I can find a teaching moment here. The famous Tristan chord is fun to talk about and one can analyze it in a number of ways. Some are better and some are worse — each way is a reflection of the analyst, not of the chord itself, which is indeed just a bundle of notes.

So gather 'round. I will analyze the Tristan chord as a case study out from which you can zoom and equip yourself with an analytical alignment that will serve you as you seek to understand music, or at least allow you to farm XP from the little pigs who dawdle around in YouTube comment sections. Part of the process will be to summarize and apprehend competing analyses. It's only fair! Even the wrongest ones can reveal a glimmer, a thrice-refracted morsel of truth. If you're like me right now, you have nothing better to do.

What Are We Doing When We Analyze Music?

I despise what I call "word-thinking," where fussing about this or that definition stands in for real communication. Just say what you mean, and if a word could get misinterpreted, either pick a different one or define it yourself and keep moving. The truth is that, outside of something like mathematics, words have fuzzy, context-dependent meanings and in fact you wouldn't want it any other way. It is not so unlike chords! Hmm!!

I thus want to take just a moment to distinguish analysis from theory in music. Analysis looks backwards and seeks to explain. Theory looks forward and seeks to generate. They overlap big-time but those goals aren't quite the same. To me, the most interesting spot in which to put yourself when you're thinking about a mysterious moment in music is the moment of its conception.

What was Wagner thinking moments before composing the Tristan chord, or really, the whole motif, the phrase that would become so recognizable and so bedeviling? And then once he played or wrote down that moment, how did he react to it — how did he proceed? Every great composer improvises and most compositions are something like frozen-and-trimmed improvisations. You can stumble or otherwise generate a little seed of something great and then it's up to your ears and your imagination to leverage it: to explain to yourself what came from your subconscious (analysis) and then generate more of it (theory).

My goal in picking apart the Tristan chord and its surrounding music is to figure out what kind of idea gave rise to such a special moment but also to theorize how Wagner squeezed more juice out of it than just four bars. What is the principle behind the moment? Selfishly, I would like to be able to compose, or better yet, improvise-by-ear music that sounds like the Tristan prelude. I want to think, feel, and hear like Wagner (well, maybe not too much...there's that whole...never mind...).

So let's do it. The final groundwork is to announce some premises and then to survey the analytical landscape. Then I will offer my own explanation, which I believe will fulfill the premises better than competing analyses. The final test will be the analysis' effect on a musical mindset: which analysis opens you to hear, feel, or understand the music best? And which opens you up to play, improvise, and compose "more Tristan?"

Premise 1 — Music is meant to be heard.

Notation and spelling can and do give clues but an analysis loses its validity if it requires you to ignore your ears. A good analysis may transform your ears! But it will not ask you to turn them off.

Premise 2 — Occam's Razor.

Prefer simplicity and elegance to convolution and contrivance. There is much music that is irreducibly complex and takes a lot of work to unpack, but in those cases it is especially important to reach for simplicity. As analyses compete, all else being equal, the more straightforward one should win.

Premise 3 — History matters.

Composers can reach back and indeed forward in time, but any analysis that asks us to think way outside of what was available to a musician at the time s/he made music is in trouble from the start. Tristan und Isolde was composed in the 1850s. That is shocking — it is radical music for that time period, when Brahms was only in his twenties, for instance — but it is nonetheless true.

Premise 4 — Know thy neighbor.

Lazy analysts miss this one. Look for other musical moments that resemble the one you're focusing on. Does your analysis explain those, or at least comment on them? This can happen within the same piece — indeed "the" Tristan chord finds many cousins throughout the prelude and the whole opera — but you owe it to yourself to find resonances in other works, even by different composers. Learning Mozart helps you understand Beethoven, and so on.

Sound good? You are allowed to disagree with any of my premises, and maybe this marks a good time to stop reading in that case, but musical people should find them reasonable. We are after a straightforward, historically-literate, applicable-to-similar-music analysis that comports with what we hear.

Now let's peek at the moment in question and review some hypotheses about what it is and what it means. (Try to spot which premises are fulfilled and which are broken in the incorrect, or at least suboptimal, analyses.)

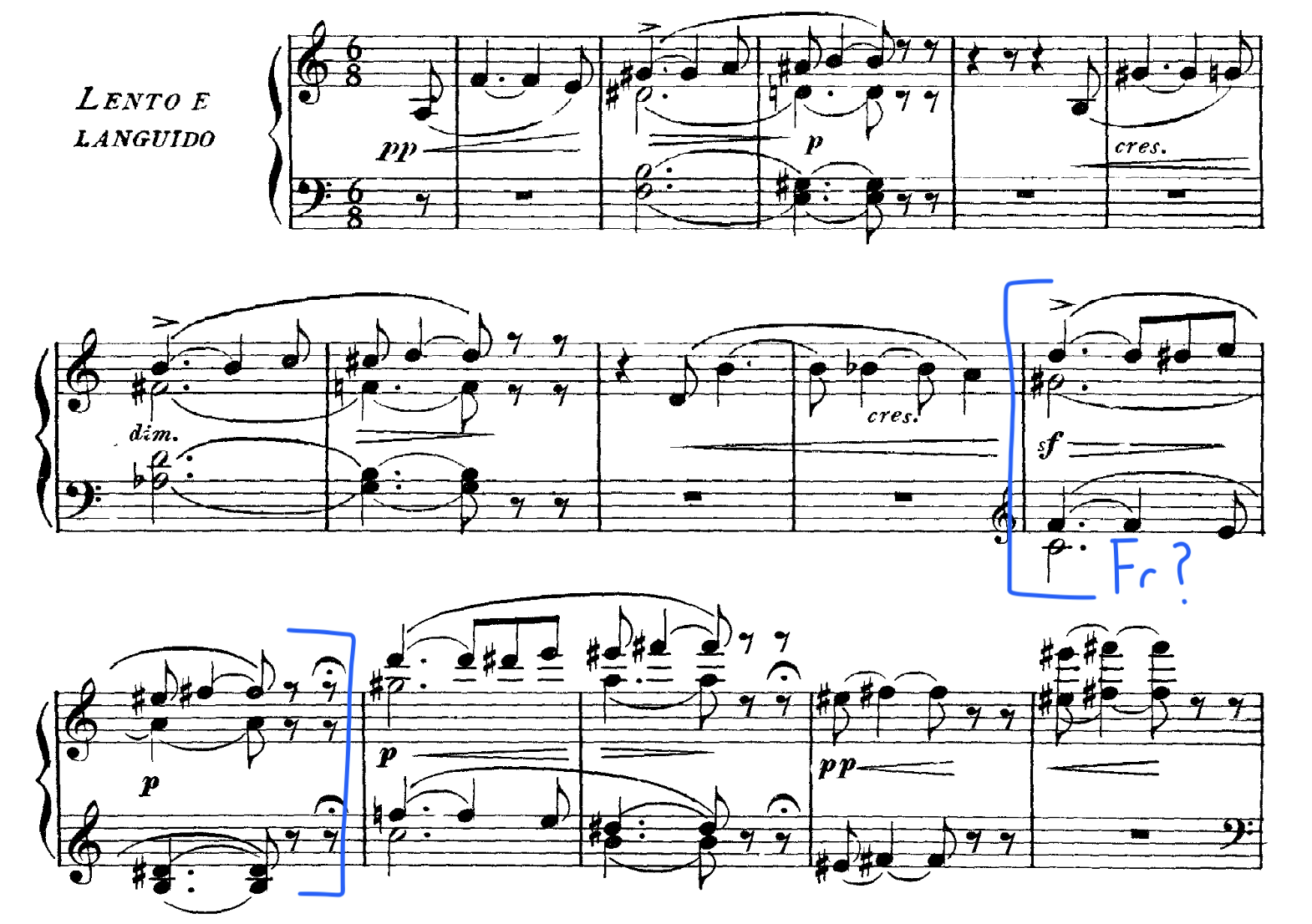

The moment in question is the very opening to the prelude, or Vorspiel, of the opera or Musikdrama. This is the first thing heard when the lights go down and the 1865 crowd silences their cell phones.

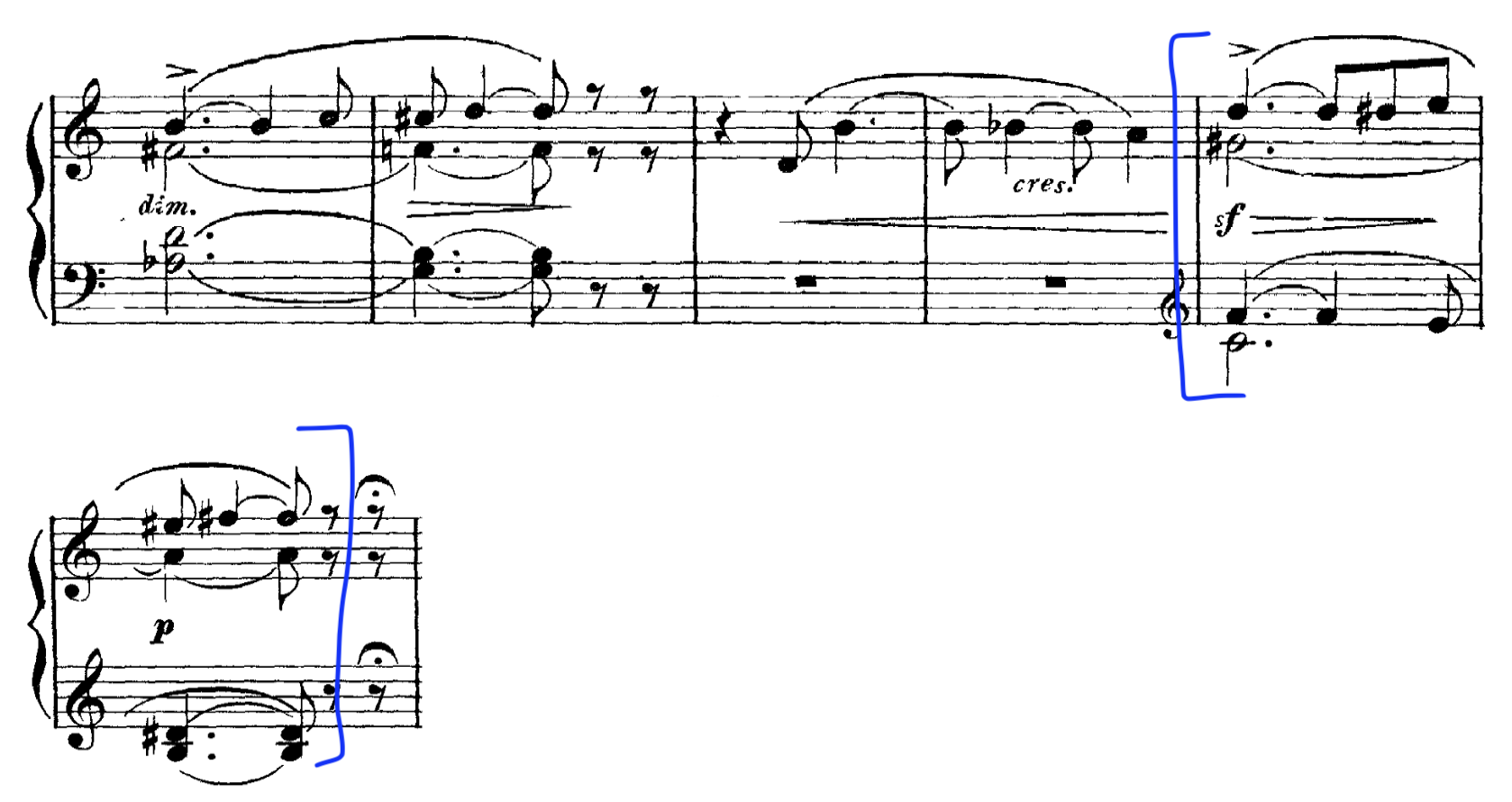

(I will use a piano reduction for simplicity, but I will draw on the full orchestral score when it is helpful.)

You are going to hear hours and hours of music after this. A performance that begins at 5:00 PM lets out at like 10:15. It would nice not to be irreparably confused after five seconds!

"The" Tristan chord is the first chord: F-B-D♯-G♯.

OK — before we get all vitriolic and whatever — can we agree that this rocks? (Additional premise/recommendation: only analyze good music that you like! A strong analysis should make you like it more!)

What's the big deal?

For one, it's spelled funny. The sonority played on its own would be identified as F half-diminished, but that chord would be spelled in flats. E♯ half-diminished would match the top three voices but that bottom F disagrees. Spelling is not the only concern, though (and indeed, I will cast doubt later on spelling-as-the-end-all-be-all); it is the chord's motion that makes it so cool and mysterious. The phrase ends with an E7 chord in root position. Along the way, the top voice slides by half-step to produce some other sonorities — we must ask if these are "real" — but a naïve first step asks, "F half-diminished to E7? How does that work — what key are we in?" F half-diminished "belongs" to G♭ major or E♭ minor and E7 sets up A major or A minor.

Now our analytical job is to make sense of this music. Is the chord we hear a real chord at all, or some illusion produced by a trick? If it is a real chord, how do we explain its motion, and better yet, how do we imagine Wagner coming up with it in the first place? I also want to take care to peek around at comparable moments in the piece. That exact chord, with the same "resolution," appears in numerous spots; it also appears in exact transposition; moreover, countless moments feature music that sounds a lot like that opening but are not exact transpositions. Your ears do not lie: those moments are related, especially considering that Wagner is the composer associated with motivic recurrence and development. It is clear to me that the semantic meaning of that opening motif occurs again and again throughout the work and Wagner expects his audience to hear that.

If you are not yet ideologically captured by a camp of analysis, now is your chance to hypothesize an explanation. What's going on here? (And do me a solid, poke around the piece... m.10 presents the first nontrivial puzzle related to the opening.)

Here's what others have said:

The Early-Atonal View

One analysis, which drips with twentieth-century modernism, labels the chord and its motion as "nonfunctional," which is to say, divorced from a sense of key or even the tonal system altogether. The argument goes something like: there is no way to analyze the chord from a functional perspective, and we know now that German classical music would become atonal half-a-century later, so we can trace the roots of atonality back to somewhere, and that somewhere is here. One might say that Wagner lit a fuse that would doom the tonal system or that atonal music became inevitable when that chord was composed.

No. Using the word "atonal" in 1857 would be like using the word "Democrat" in Ancient Egypt. It is true that Wagner was a radical, but not that radical. This view holds that 99% of Tristan und Isolde is tonal and this strange moment is not. I and others contend the true number is 100% and that we can find a tonal rationalization of this chord and its voice-leading.

That said, there are two thoughts I sympathize with in this analysis. For one, it is true that Wagner's chromaticism would make Mozart blush, and Schönberg's eventual leap into free atonality follows experiments in hyperchromatic Romantic music which share a lot of DNA with Wagner's. Wagner is some kind of "midpoint" between Mozart and Schönberg. There is a sense in which you can drench and obscure tonal music with pungent chromatic music so that the sense of key all-but-disappears. But this is not that music; it is a bridge too far to label it as "atonal." Not to mention, atonal means only the absence of tonality; it is more of a null hypothesis than anything and does not have explanatory power. My other sympathy with this view comes from a follow-up that does have some explanatory power. Atonal chords are organized not by function or key-area but usually by interval content and possibly symmetry. This is a step in the right direction for my interpretation of the chord — the intervals matter and symmetry matters — but intervals and symmetry need not destroy tonality.

Let's toss this analysis and save it as a last resort. (We won't need to!)

The French-Sixth View

If the Early-Atonal View pines for the future after Wagner, the French-Sixth Views pines for the past that predates him. The thrust of this view is that "the chord" itself — the F-B-D♯-G♯ sonority — is not meaningful, that in particular the G♯ is not a chord tone and the real identity of the chord is F-B-D♯-A, which is a so-called "French Augmented Sixth" setting up E7 as the V of A minor.

There is something clever about this analysis. Indeed, those notes spell a Fr6 and the Fr6 is usually conceived as a predominant. This analysis rationalizes a tonal context and submits that Wagner is actually more conservative than you might think — he is using an old trick to write music in A minor, and you are being misled if you hear a half-diminished chord at all.

The persuasiveness of this view wilts under inspection. I say so for a number of reasons, the strongest of which being that the Fr6 analysis cannot cover related moments that Wagner wants us to group together in our ears. The Fr6 analysis is like pointing out an edge case and missing the truer, deeper principle underneath. Look at the end of the second line going into the third line:

There is no Fr6 to be found in that first highlighted bar. The only augmented sixth interval is between the F in the tenor voice and the passing D# in the soprano, and even then, the alto G# would need to be an A, and the bass C would need to be a B unless this were a "German sixth" instead, and the inversion is weird, and the chord would have had to prepare E7 not B7, … An analysis that goes, "but, but, but…" is not worth keeping.

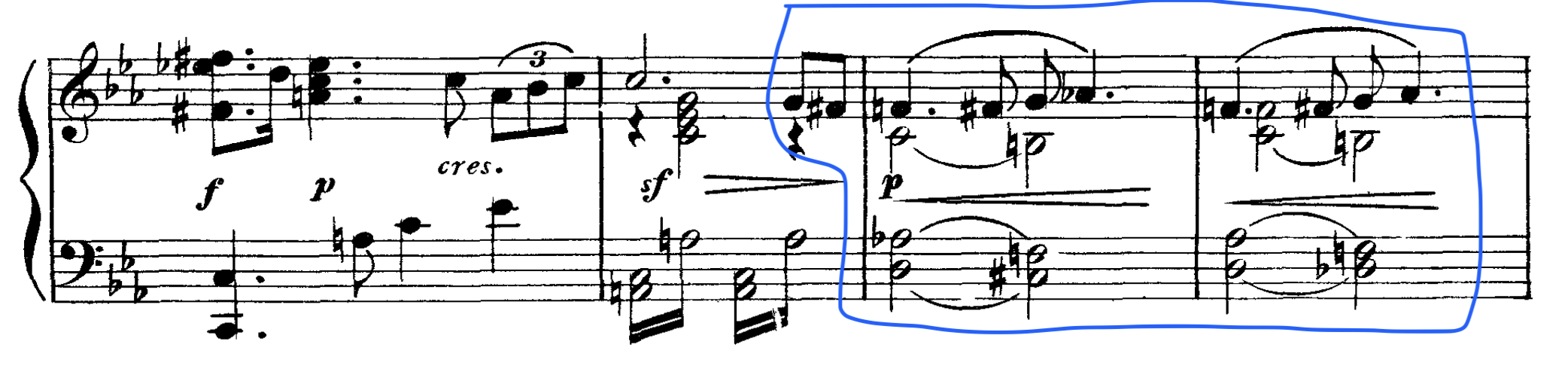

And what are we to make of this moment later in the prelude?

This must be the same idea as the opening. The melody in the lower staff tells us so. It lands on an unambiguous half-diminished chord which then passes through a Fr6 en route to the dominant. This time, instead of the melody rising to make that effect happen, the accompaniment falls. But the Fr6 reading of the opening requires one voice in the first sonority to be a non-chord-tone so that the half-diminished reading is false. The above example shows the Fr6 not as the idea's true identity but as an artifact — a coincidence! — of the voice leading.

I am aware of the following chain:

which looks something like a bunch of Fr6s going to dominants. One could argue that this is not the same idea because the leaping melody isn't there, but either way, how are we supposed to judge which moment represents the true chord? If the first note were raised (so that the first sonority were equivalent to half-diminished), that would be one thing, but is that F♮ somehow a non-chord-tone that resolves to the G in D♭ Fr6? Or, following the logic of the final soprano note of the bar revealing the truth, does the A♮ produce some kind of D♭ augmented augmented sixth chord? The Fr6-based analysis relies on a circular conceit: ignore all sonorities but the Fr6 because only the Fr6 is correct; now you see why the Fr6 is correct! Everything is a nail with this hammer. OK — maybe we put that chain-moment to the side because the leaping melody isn't there and we don't see the chromatic approach to the third of the supposed Fr6 chord.

I have seen arguments for the Fr6 interpretation based on spelling. In particular, the G♯ creates an augmented ninth — a dissonance that must resolve — against the bass F, and that if Wagner wanted anyone to hear the half-diminished he would have either spelled the chord in flats or written the bass E♯. Well, then what do we make of this, from the full orchestral score?

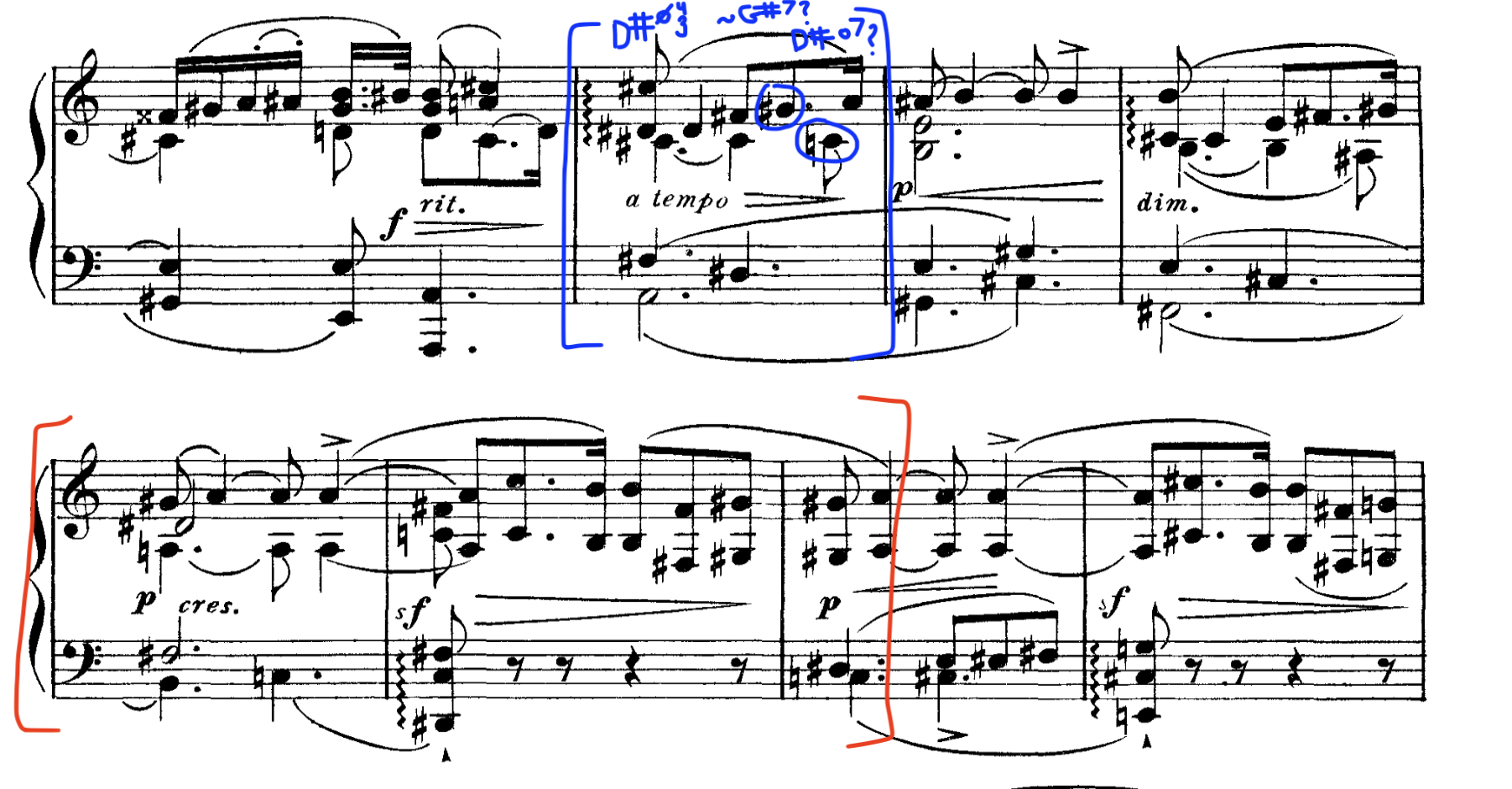

Oh boy. I have circled the melody in the middle strings. In the viola, F-E-D♯, as in the opening. In the cello, F-E-E♭! Violins play, in no uncertain terms, F half-diminished, spelled in flats, as do trumpets and trombones, but then the woodwinds are in sharps. What a mess! If the F half-diminished is false, then the brass sit on a chord with a misspelled unresolved augmented ninth above the bass, leaving that voice abandoned. An unlikely story.

Moments later, we get, after the melody goes up-a-sixth-then-down-chromatically, F, E, ...

What!? Where's my E7? A Fr6 on F requires a D♯, and it should move to some kind of E chord too, but instead we get a chord with an E♭ — a minor seventh over the bass, not an augmented sixth — going to a B diminished-seventh chord, with A♭ replacing the G♯ we saw before.

We can find another weirdly-spelled moment a few minutes after the prelude, once the action begins:

If that first chord in the highlighted chunk is a Fr6 built on D, it needs a B♯. And then we get the strange half-breed dominant chord C♯-F-B-A♭. In this example, the half-diminished chord is the only one spelled right!

Another moment that makes sense if the Fr6 chords are passing artifacts but is hard to rationalize if they comprise the core of the idea:

My take is that these examples weaken the reliance on spelling in general, knocking the Fr6 interpretation down a peg and strengthening the hypothesis that the half-diminished chords we hear are not false artifacts.

I disagree further with the Fr6 analysis when I put myself in Wagner's shoes as a composer. Of course we cannot know what went on in his mind. But I cannot get myself to imagine that he sat down and said, "I am going to begin this piece with a Fr6 chord, disguised with an unprepared dissonance, 'revealed' on the final eighth note of the bar." For one, I am not aware of any earlier piece that begins with an augmented sixth chord, let alone the French. In fact, it is hard to think of examples of the Fr6 chord in the literature at all! When I rack my brain for examples of augmented sixth chords, I come up again and again with German sixths. Moreover, augmented sixth chords are always used as intense predominants, late in a phrase once a key is well-established, as a kind of "hit the accelerator" towards something like a half cadence. We can only perceive the augmented sixth interval as distinct from the more common minor seventh because of its placement relative to the diatonic macroharmony a piece establishes. As an opening sonority, especially with the extra chromatic note that lasts seven times as long as the "true" chord tone... this just doesn't feel like the right train of thought. When I get to my own analysis, I will hypothesize a more believable compositional strategy.

I ought to mention that I am agnostic on the "key issue" in the first section of the prelude. The Fr6 camp would like you to believe that the music is in A minor (F Fr6 to E7 only appears in that key). The other zero-flat, zero-sharp key signature, C major, is a possibility. The second phrase transposes the first up a minor third to land on G7, from C's world (I wonder if the minor third transposition could have any other significance…?…), and I also hear this chunk as more in C than in A minor:

If I had to pick, I'd pick A minor, though I don't find much satisfaction either way, or in declaring large chunks of the music in this key or that key in the first place. What does it mean to be "in a key" and what does that add to the analysis? The prelude does not work towards a big cadence that grounds the music in an undeniable tonic. The climax is on F half-diminished (lol) and then the music dies down to a whimper before the first vocalist enters. F (or E♯) half-diminished plays a special role in the key of B major, the final tonic we hear in…five hours, though I admit it is not unreasonable to read into that knowing what we know about the composer. Another analysis I will bring up soon does read into that. But rather than fuss about the key, a global property, I will note that Wagner shows that there can be degrees of tonal rootedness: it's not 0 or 1, Webern or Mozart. The prelude is not atonal because its main elements are major, minor, dominant, and half-diminished chords. But by denying cadences, heaping on chromaticism, and playing with symmetry, Wagner floats between the poles. The functional harmony is glued together a few moments at a time such that a global key does not stand out to our ears. It is a bit like building a map of the world out of charts that you stitch together: each continent might look good when you zoom in but the whole map gets a little funky and bent when you step back and take it all in.

It's time to move on. The problem with the Fr6 view is that it's just a pattern-match that leads to circular reasoning. Yes, you can find pitches that sum up to a Fr6 in the opening phrase and indeed in spots later on. But the idea crumbles under scrutiny. Tons of other moments, which, again, I claim resemble the opening such that Wagner wants us to hear them as related ideas, cut against the Fr6 analysis unless you presuppose that the analysis is true — no bueno! Finally, the Fr6 analysis leads us to imagine an impossible-to-believe compositional mindset in Wagner, one which cuts against all the norms that the Fr6 would seem to uphold. However, let me note my sympathy for this view. The Fr6 chord as a general phenomenon, rare as it may be, comes from the impulse to close voice leading gaps, which is an impulse Wagner shares. Take iiø4/3 to V in A minor: a B half-diminished chord in second inversion moving to E. The D natural in the Bø4/3 chord moves most smoothly up a step to E. That's one diatonic step. But it's two chromatic steps — a gaping chasm! Raising the D to D♯ shrinks that gap and produces the Fr6 because F to D♯ is an augmented sixth which pulls toward the octave E to E. That's a specific instantiation of a general principle that Wagner made better use of than any of his contemporaries, and it points in the right direction for the truth of the Tristan chord (though it does not reveal the full picture). An incorrect analysis can nonetheless shine some oblique light on the truth.

The Schenkerian View

I have something of a soft spot for Schenkerian analysis while I acknowledge its weakness as theory. I like it because it feels inherently musical as opposed to an imposition by outside sciences, and, even if Schenkerian principles do not possess the rigor to withstand an adversarial scholarly onslaught, I feel that when I go through the motions of piecing together a Schenker graph, I learn something about the music. It's good exercise for the ears.

The briefest of overviews: the two main verbs of Schenkerian analysis are prolong and depend. Your job as a Schenkerian analyst is to tease out heirarchies between notes. Notes on lower levels of heirarchy depend on other notes and therefore prolong them. For instance, a neighbor tone, like F♯ moving to G above a C major triad, depends on that G and prolongs its function without contributing a competing function. A cascade of arpeggios may decorate a simple melody in the top notes of the arpeggios; the top-note melody exists on a more prominent heirarchical level than the other notes that arpeggiate beneath them, so the arpeggios depend on the melody (rather than the other way around) and thus serve to prolong it. If you buy this, you earn a license to abstract away the foreground of a composition, blotting out dependent notes in order to reveal the more significant, more independent notes, which sets you up to identify a contrapuntal skeleton to a tonal piece rather than a one-chord-at-a-time harmonic one. The big idea is that much of harmony is a kind of coincidence of simple counterpoint which unfolds on multiple layers of heirarchy at once; scalar melodies and bass arpeggios churn in the background while the foreground decorates them.

It is a cool idea. I would bet most musicians would agree that some notes can be more important than others, whether you're talking about performance, composition, or improvisation, and the exercise of seeking those out pushes us to listen deep. If you take the Schenker too far, though, you get into paranoia territory, melting off the personality of music, denying in-your-face harmonic choices, and instead looking for some Grand Scalar Conspiracy.

What does this view have to say about the Tristan chord? You can find a number of Schenkerian readings and you can go read them for yourself if you want the full bouquet of details. I enjoyed John Rothgeb's 1995 article I found on Music Theory Online, which is only "lightly Schenkerian," acknoweldges measure 10, and admits that the ear begs for a half-diminished reading, going so far as to suggest that Wagner used later half-diminished chords as a sort of "pun" with the Tristan chord itself. Rothgeb says that the soprano voice G♯-A-A♯-B "should be understood as an indivisible entity, and indeed one that properly belongs above the bass note E of bar 3." The E7 is the target, and all the preceding notes, and indeed the notes that comprise the Tristan chord itself, live along tendrils that slide towards the target. So, to compose "a" Tristan chord, you pick a target — let's fix a dominant chord for simplicity — and then "back up" the voices, not too far, fill them up with some springy potential energy, and then let them slide into place, accepting possibly pungent along-the-way sonorities.

I like aspects of this idea but as Rothgeb continues, up crop my objections. For one, I am not convinced why the first sonority is what it is even if I accept that it is some kind of multidimensinoal ramp towards E7. Why are the bass and alto raised a half-step while the tenor starts on a chord tone that waits for a voice exchange with the soprano? Why not raise two voices a whole-step, or one half one whole, or why not lower a voice instead? The reason seems to be the idea of a "pun" with later half-diminished chords, but that just admits that the chord might as well be called half-diminished in the first place! If Rothgeb said the Tristan chord is indeed a half-diminished chord whose purpose is to slide to a dominant chord, I would congratulate him — in my view, that gets you almost to the analytical finish line. But instead he postulates the existence of an invisible "elided" A minor chord before the first chord, as if we are dropped in medias res to music that began a moment before we arrived. (I suppose you could be forgiven for being five seconds late to a five-hour opera.) The point of the elided A minor chord is to show the Tristan chord itself as a wiggle between A minor and E7, and more than that, to hypothesize a compositional strategy on a longer time scale, namely an ascending A melodic minor scale as the background of the composition up through the deceptive cadence in m. 17. He graphs the idea, showing, on the top grandstaff, the main notes with open noteheads and the dependent notes with filled noteheads, plus slurs that show middleground motions, and, on the bottom grandstaff, an abstraction that filters out all but the background:

(John Rothgeb)

This analysis may have some truth but it is a non-sequitur! I agree that the main thrust of the first 17 bars is an ascent to that high A, which indeed stops at every station along the scale, but that is a separate question than the specific details of the opening Tristan chord and its cousins that appear during the journey. That this view requires an elided first chord weakens it, and either way, at the end of the day, this analysis does not tell me why the Tristan chord is what it is, why it sounds the way it does, or why it should move the way it does. What I will hold onto, though, is the observation of its closeness to its target dominant chord — there's something there.

The "Just Wait Five Hours for B" View

I have to mention just one more analysis. It comes from one of the two YouTube videos that spurred this post in the first place. I don’t even want to link to the video to be honest. On one hand, it is wrong and is as flimsy as a sandcastle in a tsunami. On the other hand, it is novel and is wild enough to make me laugh — admirable. And, like all but the very-worst analyses, it can crack open the door towards some kind of insight.

This analysis begins by claiming that the spelling of the opening is fine as it is and that the Tristan chord is the chord you hear right away — good start. But rather than deal with the how the chord voice leads in the opening or anywhere else in the prelude, the analysis asks us to jump ahead to the final moments of the whole opera. On my score, that is 438 pages later. Let's take a look:

OK! I see it! F, B, D♯, G♯. I like that we are highlighting this ending, which is hip-as-heck. The G♯ pulls up to A at the end of the bar, just as in the opening; then there's an A♯, an accented passing tone, moving to B in the next bar, over an E chord...but wait...it's E minor. Oh, it hurts so good. And...mmm...yes...that fourth beat gives the flavor of C♯ half-diminished...oh, baby, I'm gonna...all over a B pedal...sweet release, death-as-orgasm, B Gott-dang major, heil Wotan!

Exact spelling notwithstanding, ♯iv half-diminished to iv minor to I major freakin' rules. It's sort of the plagal mirror-image of Ger6 V7 i minor. What else is cool about this? Well, the prelude begins in a zero-sharp, zero-flat key signature, and the whole opera ends in a five-sharp key signature. Those keys do not overlap much. F half-diminished is about the best you can do as a compromise! It belongs natively to neither key but can work as an exotic chord, two moves away from the tonic, in both.

The YouTube analysis, unfortunately, overplays its hand when it reaches back to the opening. The claim is that the Tristan chord from the prelude is a G♯ minor triad over an auxiliary F, that is to say, a so-called slash chord. Why? Because G♯ minor is the relative minor to B major (make sure to hold that in your head for five hours), and F, being a tritone, the furthest interval, from B, represents the ultimate tension, a great opposition that must be overcome. This, apparently, has to do with Schopenhauer.

Dang. You lost me. First things first, why not, uh, B major over F? Or B minor for that matter? If the entire opera, hours and hours of music and drama, is all a titanic, Teutonic crawl towards B major, which represents the finality of death, why substitute all-important B for a chord that shares only two of its notes? Just because? It's not like Wagner was afraid of a chord like B-major-plus-F; the downbeat of measure 17 way back in the prelude is a B in the melody over an F major triad (is that supposed to be like, life or something?). I will concede that if any composer would think of something so high-and-mighty, so glacial, so self-important, it would be Wagner. But we still have to face the facts.

Where this analysis really faceplants is when you ask it to explain anything else that happens in the music. What about measure 6, or measure 10? What do those represent? How do they further the mission towards B? What about measure freakin' 3, the E7 that follows the Tristan chord that retroactively makes it so interesting from a voice-leading perspective? The analysis boils down to "the beginning is actually the ending" which leaves everything in the middle dry and unaccounted for. Sorry — into the trash with ye. You get a consolation prize for opposing the Fr6 view and a commendation for thinking big and weird.

The Answer

It is time to announce the truth. Let me list what I like about the above four analyses despite their ultimate wrongness:

The Early-Atonal View gets us to think about the intervals of the Tristan chord and the symmetries or near-symmetries of chords like half-diminished and dominant.

The French-Sixth View centers on a chord whose purpose is to shrink voice-leading distance to a dominant chord.

The Schenkerian View recognizes the importance of small-step voice leading towards a target chord and reminds us that contrapuntal motion — that is, motion in each voice independently — can lead us to build strange chords that move strangely.

The "Just Wait Five Hours for B" View gets us to look for other instances of the same or equivalent or similar chords throughout the opera and gives us a chance to soak in that verklempt ending.

Now we must synthesize. I want to explain the sound, function, and compositional origin of the Tristan chord in a way that comports with "the other Tristan chords" in the prelude and later, in a way that does not appeal to spelling and, ideally, in a way that can germinate into theory — that is to say, so that you, fellow musician, can take an idea and compose or improvise music that descends from Tristan.

On sound: it is a half-diminished chord. The Tristan chord is indeed the first chord you hear, F-B-D♯-G♯, and when you hear that pungent half-diminished sound, you are not misled. Moreover, if later on you hear half-diminished chords after the same up-a-sixth-down-chromatically melodic motif, you are correct to group them together with the opening phrase.

On function: the Tristan chord does not function in the usual half-diminished way, as iiø7 in minor or viiø7 in major. Instead its function is to move towards a dominant chord by passing through a diminished-seventh axis of symmetry. This is the key to understanding how to come up with a "Tristan-like phrase." I will spell this out in detail momentarily.

On compositinal origin: Wagner was a progressive who sought to push the techniques of the past to new levels of intensity. Modulation had been a big part of classical music for a long time by then, increasingly so in the nineteenth century. Close modulations (most often by fifth) work by applying a single accidental to a key signature and by exploiting the fact that the fifth of a chord is the root of a chord a fifth away. Simple algebra! But more remote modulations by third appear in Romantic music as early as Beethoven. One has to apply three or four accidentals to the key signature in those cases, but the common-tone symmetry strategy still applies. As an example, when Schubert, in his beloved C Major String Quintet, modulates from G to E♭, the pitch G acts as an anchor, first as the root of G, then as the third of E♭. To pull off such a move smoothly, one has to permute the voices or else face the ugliness of big leaps or clunky parallels. G (root) becomes G (third). B (third) moves by half-step to B♭ (fifth), and D (fifth) moves by half step to E♭ (root). Viewed that way, the journey seems not so far. Why and how does this work? A tiny speck of math: there are twelve chromatic pitches. Triads have three notes, so the most evenly-spaced symmetrical triad is the augmented triad built of major thirds (four semitones). When triadic music wants to move by third, the smoothest way to do so is by passing through the augmented triad as an axis of symmetry. G major shares two of its notes with the E♭-G-B augmented triad and the third lies just a half-step away. Same goes for E♭ major! It must! So, even though we don't hear the augmented triad (that would be so pedantic), our ears pass through it. You can think of G-major-to-E♭-major as factoring into two moves which happen simultaneously: D moves to E♭, producing the augmented triad, which is provably the most mobile triad — it is as close as you can get to as many other triads as possible — and B moves to B♭. G major and E♭ major are like 120º rotations around the axis of symmetry. (Moving to B major, from either G or E♭, would follow the same principle.) Note that minor triads are just as close: raise any note in an augmented triad rather than lower it and you produce a minor triad.

The axis of symmetry for four-note chords is the diminished seventh chord, built of minor thirds. Let's repeat "the Schubert trick." Take B diminished-seventh: B-D-F-A♭. (You should realize by now that symmetry requires us to identify enharmonically equivalent pitches like G♯ and A♭.) Perform the same transformation as before: raise or lower one note by one half-step. What do you get? Any lowering produces a dominant: B♭7, D♭7, E7, or A♭7. Any raising produces a half-diminished: Dø7, Fø7, G♯ø7, or Bø7. Here we find the Tristan chord, Fø7, "just across the border" from E7, both a single half-step-in-one-voice voice-leading from Bº7. This insight, to me, 1) explains how the Tristan chord moves, 2) allows us to trust our ears that it is a half-diminished, not some illusion, 3) only requires voice-leading "technology" accessible to Wagner in his time, 4) opens the door to see how comparable "Tristan-like" phrases work, but 5) does not force us to cross the Rubicon into atonality.

As a single thesis statement: the Tristan chord is a half-diminished chord distinguished by how it moves to a dominant chord through the axis of symmetry of the diminished-seventh chord.

Two corollaries:

A descending chromatic melody announces the Tristan chord and a representative Tristan phrase contains an upward chromatic melody.

A “Tristan phrase” begins on a half-diminished chord, ends on a dominant chord, and features chromatic outward motion in the outer voices.

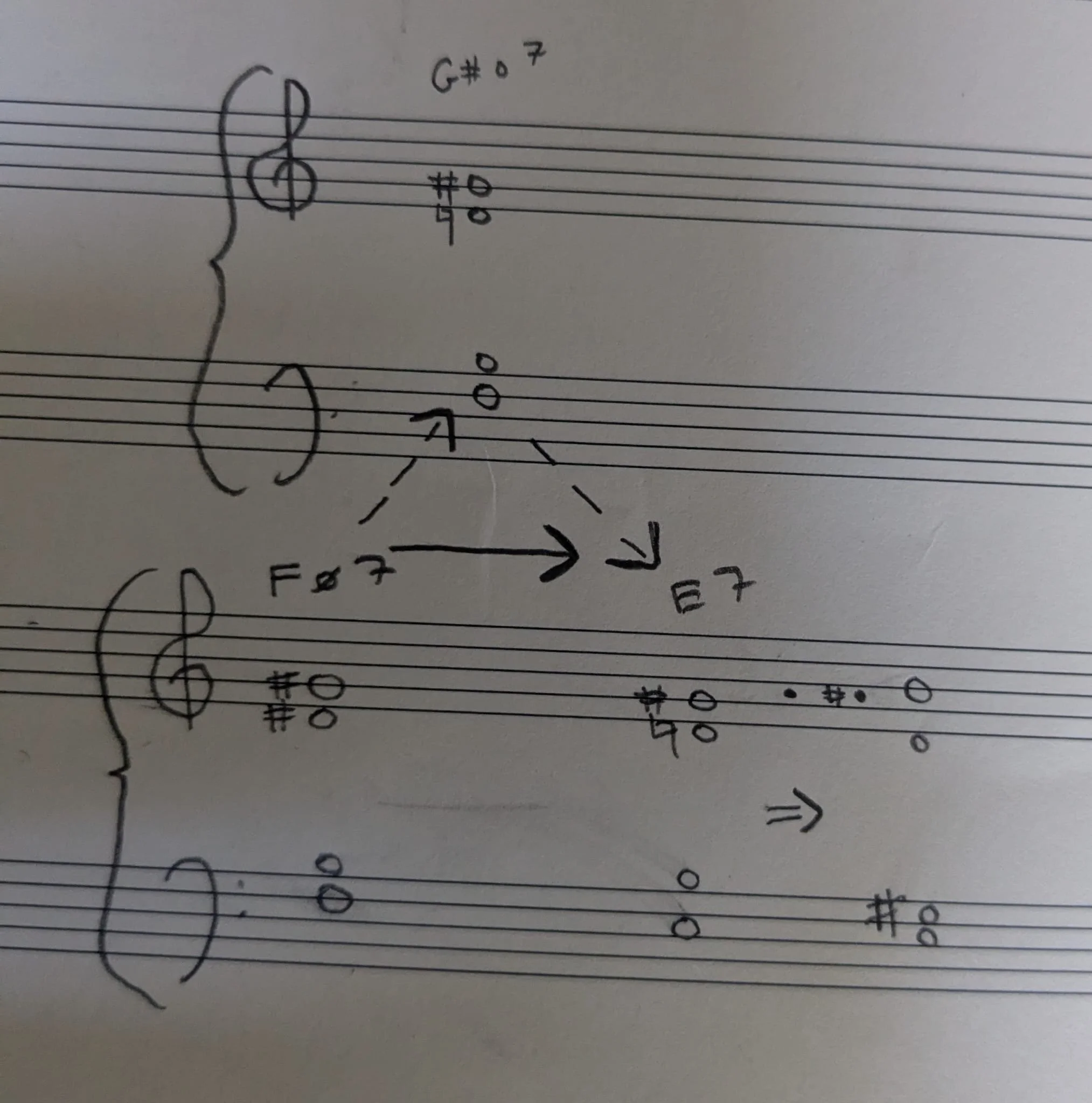

This diagram shows the voice leading path "factored through" the diminished-seventh (as well as the voice exchange that accounts for the slightly more open spacing of the E7 compared to the Fø7):

Now I want to dig into some details that, I think, show the correctness of the analysis by showing how it aligns with other attributes of the composition. I will do my best to preempt objections along the way.

Why Don't We Hear the Diminished-Seventh Chord?

For the same reason you don't hear the augmented chord when Schubert modulates from G to E♭: symmetrical chords are unstable and unsatisfying and are, by design, the least tonal triads and seventh chords. Half-diminished and dominant are not exactly stable but they are tonal and by no means objectionable to our ears or the ears of an audience member in the 1850s. Wagner is a composer, not a theorist! It would be pedantic and plodding to boom-boom-boom include a diminished-seventh chord between the two more beautiful chords. Think of the diminished-seventh as an axis of symmetry: a piece of geometry more than a sonority.

And yet! If we peek a bit later, we can find lots of diminished-seventh sonorities, and what's especially interesting is that they often bump right up against the neighboring dominants, such that the "pass-through" becomes literal.

In this example, I split hairs to show what I mean (a less paranoid analysis might call that final beat all a dominant with a flat ninth, which I accept but add that such a chord belongs to the same universe as the idea I laid out):

Here's perhaps a more interesting example, where a dominant chord transforms into a diminished-chord via a single half-step voice leading, which is "undone" in another voice in the next bar:

These examples are not "Tristan chords," meaning that Wagner does not expect us to hear them as reprising the opening motif. But I find it noteworthy that they share voice-leading DNA. Zooming out from the Tristan chord itself, this huge composition courts and deserves praise for its liquid form, so unconventional, with motifs and ideas twirling around and through each other. The harmonic principle that unlocks this effect, that melts the form into a liquid, is the symmetry that reveals chords to be closer to each other than older "rules" would have us believe, so that Wagner can choose from a full hand of on- and off-ramps at every point. The diminished-seventh serves as the middle junction. You hear it only sometimes but feel it always.

What About the In-Between Melody Notes?

We owe it to the Fr6 crowd and the Schenkerians to account for the A♮ and A♯ that connect the G♯ to the B in the soprano voice. Easy: they are passing tones that arise because of a melodic motif that we will hear countless times across the opera. I have heard the four-note upward chromatic scale described as the "desire motif" — fine. The A is a standard off-beat passing tone; the A♯ is an accented passing tone. Their symmetry relative to the barline mirrors the symmetry of the harmony itself! I find it far easier to stomach this interpretation, which pushes the A and A♯ to a lower level of hierarchy than the surrounding true chord tones, than to call the G♯ an unprepared dissonance, a pseudo-apoggiatura, that dwarfs its resolution. Wagner in general but especially in Tristan und Isolde crawls through melodies and harmonies by half-step; that's a huge part of the sound of the opera, with all the passing tones that entails.

(A reminder.)

Why Does the Spacing/Voicing Change?

It would be slightly easier to spot the closeness of Fø7 and E7 if they were presented with the same chordal spacing. In the opening bars they are both presented in root position but the Fø7 has its third in the soprano while the E7 spreads out so that its fifth is up top. The tenor voice does the opposite: fifth-to-third. There isn't much to say here. Overly-parallel chord progressions are for dorks (unless you are Debussy, who can pull it off, and even then, he is tactful). Any composer with an ounce of subtlety will expand and contract chord spacing. If you want a deeper reason, you can draw on the so-called "longing" and "desire" motifs, downwards and upwards chromatic scales respectively, which, pitted against each other, create contrary motion. The chord moves down while the melody moves up. It's the oldest trick in the book but it necessarily opens up the spacing of the chord.

What About Measures 10 and 11?

This is a tricky spot and an important one to get right. I believe that it provides a fatal counterexample to the Fr6 analysis. The Schenkerian view can survive by pushing passing tones away and cherrypicking notes that belong to the so-called Urlinie but that does not satisfy me; I want to know how and why this moment is different from the first two phrases.

First of all, we have to admit this is the same idea as the opening as well as the exact transposition of the opening we see at the start of the line (what I am calling A♭ø7 to G7). The melody sets it up as such and the harmonic boundaries are identical: we first hear a half-diminished chord and the phrase ends on a dominant. But something is a bit off: the half-diminished is Dø7 and the dominant is B7. In the previous two phrases, the roots were a half-step apart: Fø7 to E7 then Abø7 to G7. The Dø7 is in third inversion rather than root position, and there are more passing tones along the way too. We need to make this make sense.

I am going to pull out one of my favorite analytical weapons: find the puzzle, then the solution. When you are learning it is more valuable to ask a good question than to find its answer, which may be inevitable once the question is asked anyway. So what constraints led Wagner to compose this moment, which resembles but does not match moments earlier and later?

Let's work backwards. The target dominant is B7. We might have expected B♭7 because the first two targets were E7 and G7, and indeed minor-third transposition aligns perfectly with our analysis based on the diminished-seventh symmetry. But Wagner is not a mere symmetry-robot. B7 is the V7 of E and E7 is the V of A, our leading candidate for local key area. More succinctly, B7 is a secondary dominant. A line later, we find our E7:

And the F major that follows is, by most accounts, a deceptive cadence, a fakeout that denies the release A minor would provide, which is thematically appropriate (we still have five hours and, uh, nine minutes to go!).

So we see B7's standard purpose, soon to be fulfilled. That is out target dominant. By the logic of the opening, we should precede it with Cø7. But! The "longing" melodic motifs that lead into the half-diminished chords have been unfolding according to a different pattern. The first descent is F-E-D♯. The second is G♯-G-F♯. The third transposes by another minor third (of course): B-B♭-A...G♯? The three-note sag augments to a four-note sag. OK! It is clearly the same idea. We land on G♯. Can we guess why? An exact minor-third transposition would have the melody land on A as the seventh of Bø7 in the alto voice. But Bø7 would cause Wagner to lose the important half-step descent in the bass. We want C in the bass before B7. So what's wrong with Cø7? The melody would have to land on B♭ in the alto, meaning it could only sag one step from B...that would not get the essence of the motif across. Foiled again! What else do we notice about the music before this point? Every chord so far belongs to the orbit of B diminished-seventh (or D, or F, or G♯/A♭)! Fø7, E7, A♭ø7, and G7 are each a single half-step in a single voice away from that diminished-seventh chord. It is our main axis of symmetry and Wagner seems not to want to give it up yet. So here's the puzzle: we need a half-diminished chord in the B-diminished-seventh orbit with C in the bass in order to set up B7. There is only one choice: Dø4/2, that is, Dø7 in third inversion. Think about it: the only note out of B-D-F-A♭ within a half-step of C is the B; it has to move up, meaning the chord we produce must be a half-diminished, and that chord, C-D-F-A♭, is indeed Dø7 with C in the bass. It was the only option, lest Wagner break the pattern he has so-far establised or otherwise not setup B7-to-E7, looking ahead to A minor or its deceptive substitute F major.

The harmony puzzle is solved. All that remains is the counterpoint puzzle. The smoothest possible voice leading from Dø4/2 to B7 would have the bass fall C-to-B and the other three voices rise by half-step: F-to-F♯, G♯-to-A, and D-to-D♯. Two problems: it's a little too parallel — a little dorky — and it misses the opportunity to get that beautiful ♯4-to-5 in the soprano voice, as in the previous two phrases. Hence, a slightly further yet ultimately more delicious voice leading, from the bottom up: C-to-B, as expected; F falls to D♯ and hits E along the way; G♯ rises to A; and D makes the long trek to E♯ which gives way to F♯, the true destination. The final choice is rhythmic placement of those half-step crawls within the bar. I agree with Wagner's placements; the passing octave E-to-E shines and produces a fleeting augmented triad, the subtlest wink at the symmetry principle from the world of triads rather than seventh chords.

I realize that was quite a lot of explanation for two measures of music, but I want you to understand how subtle the puzzle Wagner set up for himself is and I want to prove that there was only one solution that fulfills the constraints of voice-leading symmetry, melodic/motific identity, and tonal-harmonic goals. In my estimation, all other analyses fail on one or more of those constraints.

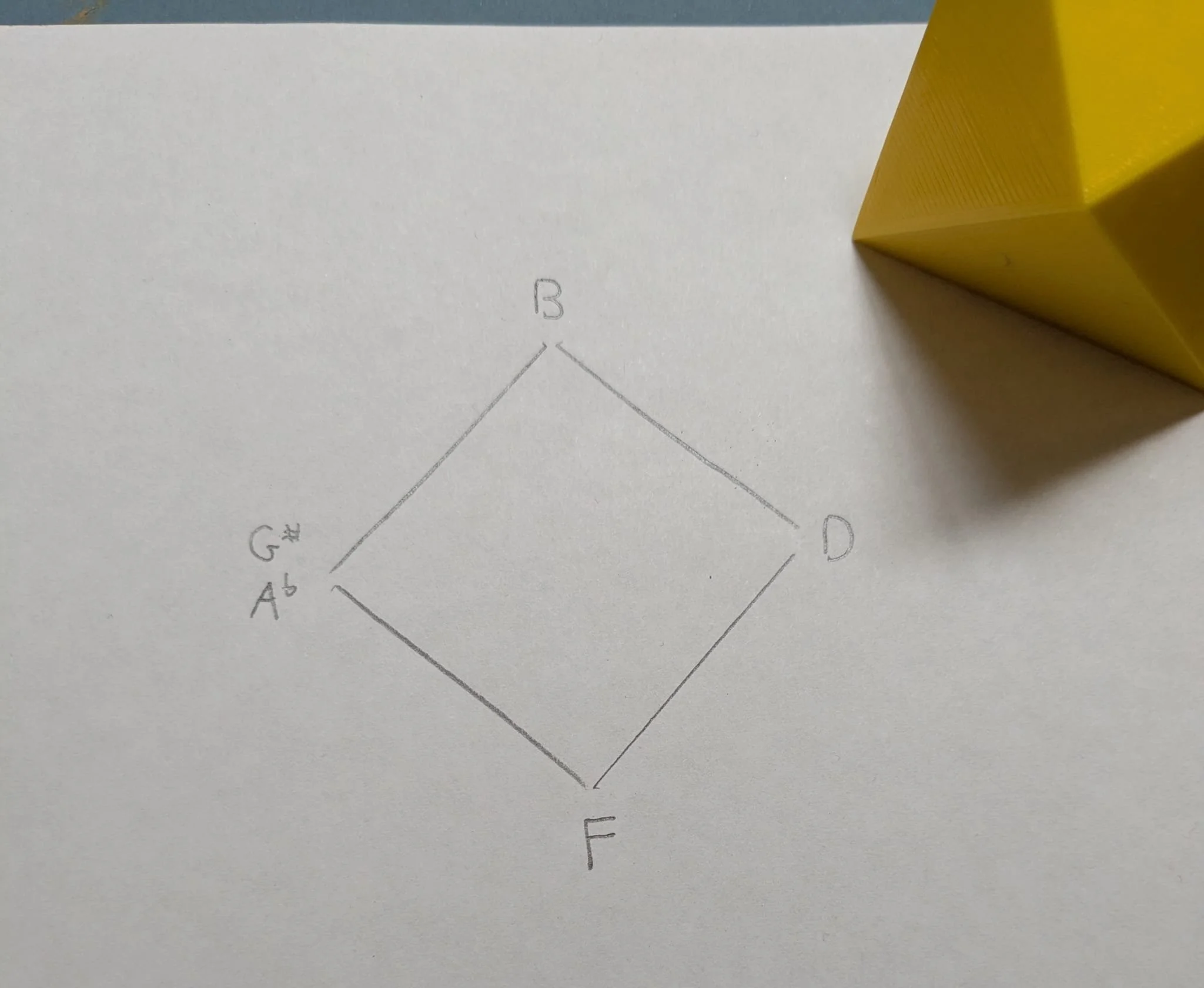

Where Else Do We Hear This Move? This excites me because in asking this question we see the range and power of the symmetry analysis. I am going to ask you to visualize a little geometry to understand the interconnectedness of these chords — it will show you a range of moves that we can then prowl for in Wagner's music. Consider the octahedron, a regular polytope with eight congruent equilateral-triangle sides:

It is the shape of an eight-sided die. Think of B diminished-seventh as the centroid, the point right in the middle of the interior, equally spaced from all eight faces. Split the eight faces into four and four — I think of the top four and the bottom four. Label the top four with half-diminished chords: Dø7, Fø7, A♭ø7, Bø7. The bottom four will be the dominants, G7, B♭7, D♭7, E7. I arrange them so that the minor iiø-V7s share edges, i.e. Dø7 touches G7.

All eight chord-faces have the same voice-leading distance from the diminished-seventh centroid: one voice must move one half-step. That means, to move from any face to any other face, you must make two such moves. You can imagine the first as restoring the diminished-seventh and the second as breaking that symmetry and creating the target chord. So, given any starting chord on the octahedron, you have seven choices of chord that are all equivalent in the sense of voice-leading distance. Or, in full generality, eight origins times eight destinations: sixty-four two-chord voice-leadings represented by choosing two faces of this shape. Try it! Pick two of the eight chords in the family and observe that you can voice-lead between them by moving two voices a half-step each and keeping the other two fixed.

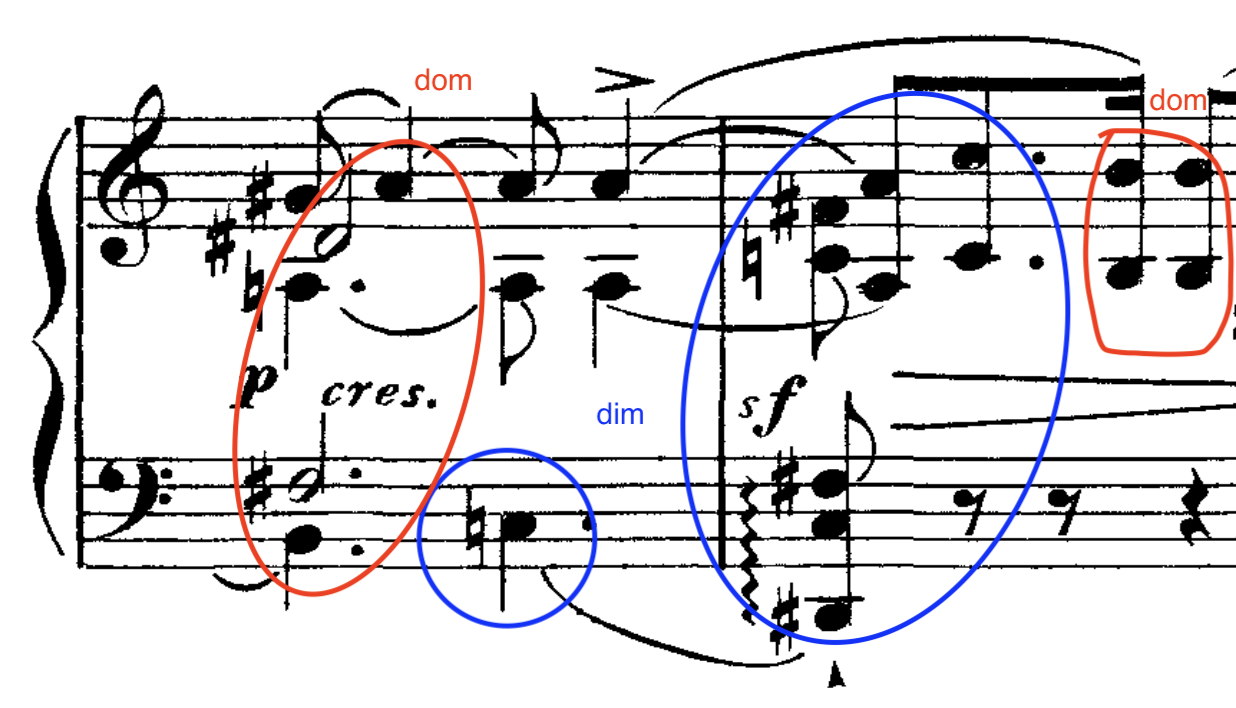

I want to priviledge two such moves. The first is the diatonic iiø-V7 in minor, as in Dø7 to G7, special because those two faces share an edge, the only edge-sharing voice-leading that picks one representative from the top and one from the bottom (i.e. one half-diminished and one-dominant, not two of the same type of chord in a row). The second is the voice-leading between two parallel faces, or equivalently, moving from one face to the unique face that does not share an edge or a vertex with it. That is the Tristan chord's voice-leading. Fø7 is parallel to E7 on the exact opposite side of the octahedron. So too A♭ø7 to G7. Special indeed!

Take this moment bracketed in blue, which is something like a iiø-V7, D♯ø7 to G♯7:

But it's a little tricky. The A hangs in the bass: a ♭9 of G♯? Or maybe the G♯ is a passing tone and the C♮ just turns D♯ø7 into D♯º7. The symmetry view renders these hand-wringings unimportant; the whole bar surrounds the D♯ diminished-seventh axis of symmetry and pushes voices to and fro by half step. So too the bars bracketed in red: everything circles around D♯º7.

Here we see a move from dominant to dominant, again through a diminished axis of symmetry, but this time "remaining on the bottom of the octahedron":

To be clear, this octahedron is a model. I do not hypothesize that Wagner conceived of his composition this way. But he felt it. He put himself in this space. Musicians always dance with geometry long before mathematicians put it into bondage. I can imagine him sitting at his piano, maybe after reading a little Schubert, and wiggling his fingers around the diminished axis of symmetry, plucking his favorite flowers. Maybe some Schopenhauerian oppositional philosophy got him to perceive the duality of Bø7-E7 to Fø7-E7 — I can buy that. But I cannot buy him sitting down and starting a piece on an arbitrary Fr6 plus an unprepared dissonance. That the underlying symmetry principle generates so much other music in the work emboldens my conviction. The Tristan chord's motion is one idea that plays great with the ubiquitous half-step melody-writing. So much more of the chromaticism comes from the same spirit, and even many of the more conventional circle-of-fifths diatonic(-ish) passages relate.

Actually — on the word "chromaticism" — what a bad and lazy word! All-too-often it stands in as a catch-all for something an analyst doesn't understand. "Apoggiatura" too. Chromaticism is a vague umbrella over a range of techniques, each of which has its own distinct logic and should be understood by that logic. Let me at least split the word in half. There is naïve or linear chromaticism which fills in vertical whole-steps with half-steps. Think of passing tones or augmented sixth chords. Then there is chromaticism based on symmetry, like Schubert modulating G-to-E♭ or indeed the Tristan chord. Wagner gets great mileage out of both! But they are not the same idea.

And no — not every single moment of Tristan und Isolde is some instantiation of the symmetry principle. It is a human composition drawing on many ideas just like any other. Allow me to summarize my analysis before finishing with some theoretical remarks: remarks that will help you generate new music from the same principles.

The Tristan chord is a half-diminished chord that moves to a dominant chord such that the bass descends via half step motion and the soprano voice rises. The form the opening takes represents the closest possible root-position-to-root-position voice-leading maneuever, which factors through the diminished-seventh axis of symmetry.

The A♮ at the end of bar two and the A♯ at the beginning of bar three are passing tones from the perspective of harmony but also fill out a melodic motif. The Fr6 vertical sonority is an artifact and does not represent the chord's true identity.

The symmetry principle — that half-diminished and dominant chords are equally spaced about a diminished-seventh, eight chords each a half-step in a single voice from the axis of symmetry — explains the Tristan chord's motion as well as numerous other voice-leading motions through Tristan und Isolde. That unity of principle enables the sense of continuity through the liquid form even as Wagner alternates between more conventional tonal moves and more exotic moves like the Tristan chord's.

Thank you for attention to this matter!

From Analysis to Theory

Enough analysis. Enough sowing — let's reap! What other music can we generate from the symmetry principle? In the four-note chord version with the diminished axis of symmetry, half-diminished and dominant are the two kinds of chords you can produce by moving a single voice a half-step. But what if you allow for more motion? Let's move two voices. There are two choices we have to make: which two voices and how they move. Envision the notes of the diminished-seventh axis of symmetry arranged in a square:

You can either move two adjacent voices (which form a minor third or major sixth/diminished seventh) or two non-adjacent voices (which form a tritone).

Let's work through the possibilities. If you move two non-adjacent voices in the same direction, you produce a chord that is two tritones a whole-step apart. It's equivalent to the Fr6 (lol) or dominant-♭5. If you move them in opposite directions you get another interesting whole-tone chord: the augmented seventh.

Herr Wagner, cook us up an example!

The D♭7♭5 (or Fr6 — that is not an invalid reading here) and C7♯4 are symmetrically arranged around the E-G-B♭-D♭ axis. If you don't buy the F♯ as anything more than an apoggiatura, fine. But I think it's playing both roles.

Now let's consider what happens if you move two adjacent voices of the diminished-seventh. Choose any two and move them in the same direction, both up or both down. You get a minor-seventh chord. I find it noteworthy that if you fix the two voices that move, the up-version and down-version are a fifth apart, giving a symmetry-based insight into root-moves-by-fifth voice leading. A minor-seventh chord is equally close to two diminished-seventh chords, so it can act as an axis around which you move from one diminished world to another! (Is it just me, or are you feeling the ghost of Barry Harris stopping by to say hello?)

The last possibility is to move two adjacent voices in opposite directions. This one makes me laugh. Why? If you move them towards each other, you produce a major-seventh, but if you move them apart, you get a 7-sus-4 chord. Is this the root of all the directionless modal modern jazz I have come to decry? Not only did Wagner light the fuse of atonality, he birthed modern jazz?

You could instead move one voice twice in the same direction. Then you either produce a major triad with a flat second (or ninth), alternatively thought of as a diminished triad with a major seventh, or a minor triad with an added sharp fourth. Beautiful, spiky chords, indeed in Wagner's quiver:

The maestro does not sit on these chords — they usually appear as voice-leading consequences — but he does not exactly avoid them either!

It takes three moves to produce a major or minor triad, doubling the root or fifth respectively. Interesting that those chords are in a sense "remote" in the world of four-note-chord voice-leading — I feel this and I suspect other composers know what I mean. Three moves in two or three voices end up being equivalent to the possibilies listed above, plus a transposition. For instance, moving three voices up a half-step produces a dominant, equivalent to moving the fourth voice down then tranposing the entire structure. This is worth exploring too because you should not expect an entire composition to center on a single diminished axis of symmetry. There are three, and the way they relate presents another puzzle. Wagner has his answers. Barry Harris has his. So does Bartók and between you and me, the man himself Beethoven plumbed the symmetry principle on occasion. From Op. 109:

Do you see all the diminished logic? And then, seemingly out of nowhere, the major-third three-note chord equivalent, the "Schubert trick," using the cube of triads rather than the octahedron of seventh-chords:

I include the early nineteenth-century example to show that interval-symmetry is not some atonal modernist idea from the twentieth century. It's bigger and older than that. It was ripe for the analytical pickin' as soon as the system of twelve (more or less) equally-spaced notes came to be. And its juice has not been squeezed dry, either. It's just an idea — not a style nor a prescription. Play with it. My final argumenative claim is that thinking in terms of symmetry will give you the best mindset if you want to challenge yourself to, say, improvise an alternative prelude to Tristan. Try it out! You can even compete — try thinking about Fr6 chords the whole time, or just following the chromatic melodic motifs, or lubing yourself up for B major way down the road. See what you can come up with. Make Dick proud.

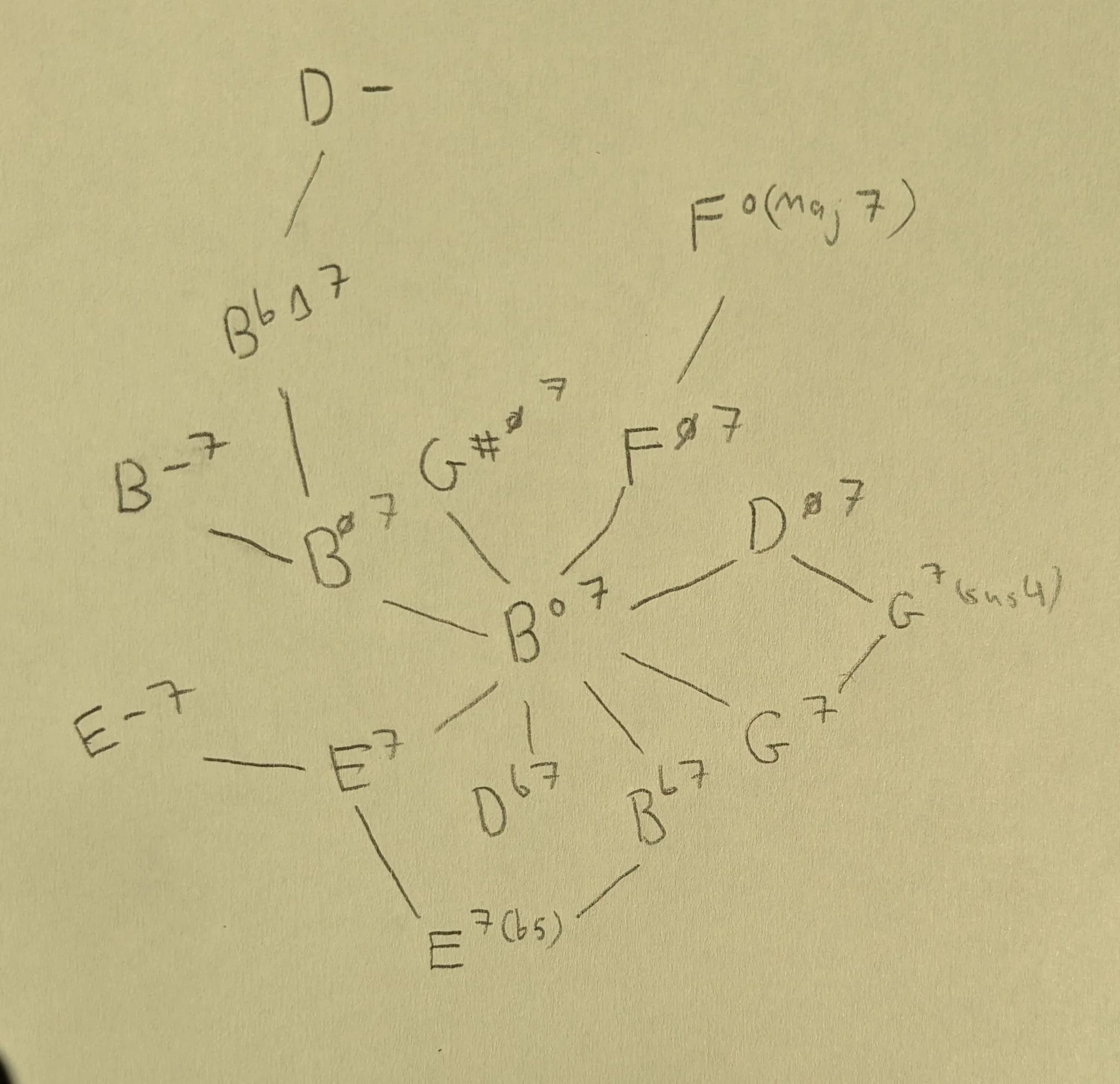

A network-sketch showing just a few of the chordal interconnections centered on Bº7. It would take more dimensions to represent the structure faithfully!