Hot nose breath; early bedtime; unaromatic seafood. “Is today the day?” Well, one of them was. I got it, along with seemingly every other sinner in this small town. Truth be told, it’s not so bad. I am more bored than I am sick. Some combo of the vaccine doing its job and the virus mutating into a highly-transmissible yet non-deadly variant. Well, whatever. They lied to us over and over and they keep lying. This moves money around, and you know which direction it’s flowing. Up and up. Sad!

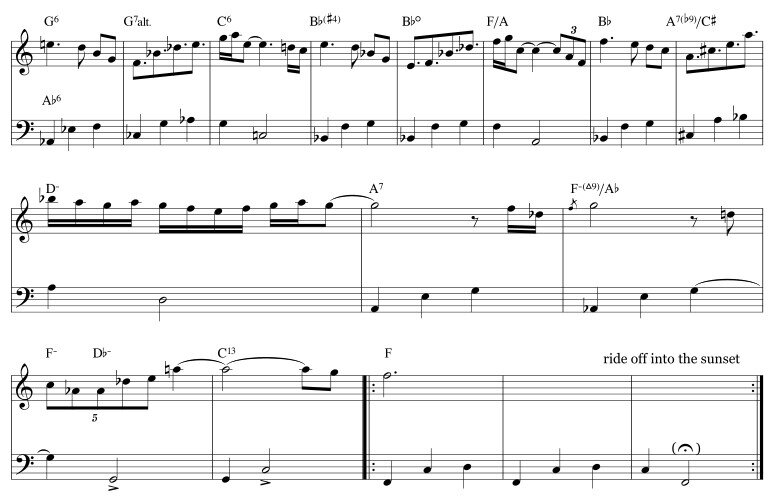

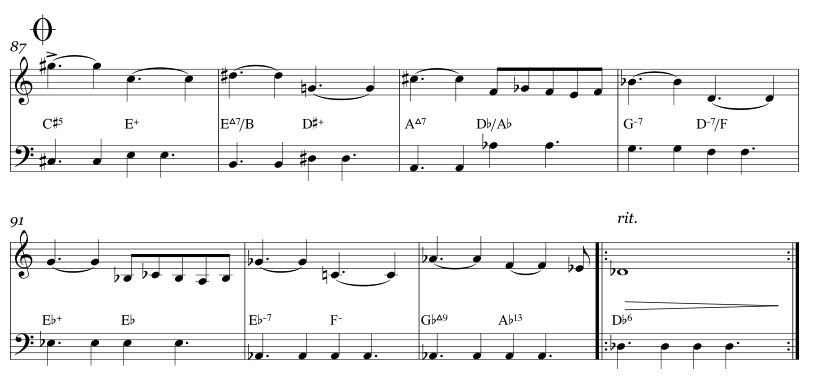

2021 was not a big year. Overall, a whimpery, achy year. I am proud of my debut jazz album Connectedness but that doesn’t feel like it “lives in” 2021. I started writing the music in 2016 and finished by summer 2017. The record came out real nice but I’m a little annoyed that I didn’t record it a little later, for mere weeks after we recorded, I set out on a path of saxophone improvement. In particular, my absolute man Caleb Curtis, the big bad wolf of the alto, master of huffing and puffing, graciously took me on as a student and lit me the fuse of Joe Allard. Without indulging the whole self-loathing mode, I’m not there yet. But flashes of true saxophone competence make themselves known; I have begun to unlock the next level, where air really becomes sound so that sound can become music. Fuck the prideful idiosyncracies and technical errors we rationalize as “personal style.” In really learning to play the instrument the right way, one blasts open the cobwebs of self-delusion and confronts the screaming, ice-cold truth of whatever it is one does. It is no coincidence that as a result of my study and reworking of my lingual technique, I am even less tolerant of mediocre jazz than before, less accepting of the truisms and the default modes of playing. Alongside breaking down saxophone-playing into its barest objective pieces, I have been naturally asking questions that break down jazz performance and composition. Why improvise? Why play a/the melody? What makes a good solo? Who cares? Such questions are profound in their stupidity (they don’t have answers) and stupid in their profundity (overwhelmingly huge). The ultimately egoistic and yet occasionally healthy mode of re-dredging these basic questions totally hinders creative output but potentially slingshots into a fruitful period, ideally that points in a new direction.

Just before I got COVID, I played three gigs in a single weekend (a first), rehearsed some new/old original music, conducted a piece of avant-garde music (gigantically poor judgment by my nameless friend who asked me to do this — did my best nonetheless), and produced a recording that features players so good they would never even think to call me. All good stuff, notches in the belt. How was it? Eh, meh. The meek-yet-truthful voice way in the back of the head: “that’s not what it’s about, man.” So what is it about? That remains to be seen. But my interest in jazz made outside the tiny, shrinking pantheon diminishes ever so. Classical music, thank God, still hits pretty Goddamn hard but I feel the stretch of universe that separates me from Vienna ca. 1791 expanding. The flames of love will burn through my log at some point, right? *shudder.* And indeed, Bartók doesn’t quite arouse me as he once did, nor do I have the patience to even press PLAY on Mahler. Mozart and Bird are still safe, for now.

And yet! I am further emboldened in my predictions about the future of music. The slothy irony is that I haven’t done/made much computer music this year. I suppose if I really believed in what I believe in, I’d peel my ass off the armchair and actually go for it. I could say “easier said than done” but that is too easily done, let alone said;;;,,,... no excuses. Somewhat lamely, I probably have to squirt Another Jazz Album [2022] out of my system before I go full Neuromancer — *sigh* — but I’ll keep preachin’ in the meantime. My imagined future of music moreover offers an escape from the quagmire of Spotify et al. Indeed, Spotify is choking out the talent that undergirds the whole industry — but I would not call it the “Music Industry.” There is more to music. Spotify is in the Instantly-Accessible-Through-Your-Device Audio Recording Industry, which is the humongous glutton sitting on the throne in the palace of music. But that industry only ascended to obese dominance in the 20th century, an exceptional century in music. Before then, it was about BEING THERE, IN PERSON, PARTICIPATING IN ONE WAY OR ANOTHER, with no replacement. And to a lesser extent, sheet music and the pedagogy that enabled a person to make music themselves. If we resign ourselves to repeat the 20th century of music over and over again, then music will just get worse and worse and Spotify will win harder and harder. But audio recordings need not be the standard of music. They will never disappear — of course. But I optimistically envision music in 2094 not as being “consumed” (ew), but just played. Nobody is not a musician. It’s a matter of tools and communication and opportunity — it’s got COMPUTER written all over it. In 2094 I hope that the youngsters snarkily look down on the boomers of the future, hitting play on their devices then just sitting there, the way we would laugh at someone who listens to baseball on the radio. Pure audio will be seen as the aural equivalent of 2D black-and-white imagery.

Perhaps. My prediction requires a generally active and curious population, or at least one whose addictive tendencies can be weaponized into action and curiosity. The 20th century way of ingesting music is well-suited to the flabby world of Wall-E, which may well be our reality. Time will tell indeed but I do not believe the future is determined historically or determined at all. We need artists and technologists to, like, do stuff, ideally as unimpeded as possible. Hence my proselytizing but also my COVID-etc-induced dismay.

That said, damn! Thomas Ades is a good composer. An heir to the Beethoven-Brahms-Bartok-Ligeti lineage. Unpretentious music coming from an environment with infinite tolerance and even lust for pretentiousness. On the other hand, Giacinto Scelsi really is of the most essential thinkers of the 20th

century — exceedingly pretentious, but it was just a matter of time before the “one note” guy came along and actually did it right. I can’t wait to play the Scelsi videogame. Tigran Hamasyan released concert footage from 2010 — I was in the middle of high school, at peak Tigran fandom, and this video reminded me why. Red Hail is still the best Tigran album and this performance legit brought a single tear to my eye. The perfect youthful cocktail of confidence, naivete, and indulgence — that music just works, undeniably. My wife and I were listening to a ton of tracks produced by Zaytoven the other day, the side-mission being to track the development of Trap from its primordial turn-of-the-millenium roots to its Obama-era flourishing, to its unfortunate yet predictable appropriation by the likes of Sprite. You know someone’s getting P-P-P-Paid when the corporate overlords slither in and decide that a musical style isn’t just for “gangsters” anymore but is in fact suitable for their imagined “general public.” Congratulations, OGs of Trap — ya did it. Enjoy the bread, but if you’re not going to make something cool and fresh, at least seed the next generation. Least you can do.

~ ~ ~

2021 was also not amazing for video games. Metroid: Dread was probably the best new game I played this year. They did everything right. The music lacked the magic needed to take it to the top of the mountain, but all the “Metroid-y” stuff was right on. Less memorable than I would have hoped, but my memory of the compact, straight-to-the-point game is warm.

The real masterpiece I played this year, though, was the “Final Cut” of 2019’s Disco Elysium, which is to Baldur’s Gate what The Witness is to Myst. Long have I dreamed for an RPG with no combat but just dialogue. Distill and perfect that mode of playing and existing in a fantasy world. The bleak yet funny politico-economic world of Disco Elysium is perhaps less fantastical than one would hope, but they nailed it. The pure-dialogue RPG with real role-playing. None of the garbage of paths that seem to branch but then rejoin like 20 minutes later; no lip service, no bulshitty filler. Actually good writing (not “good for a videogame”); real characters (no juvenile anime bozos); beautiful art (not just pixel-per-square-inch overdose). A dream come true and one that makes an important, oft-overlooked philosophical point, and very forcefully at that. Namely, that life and your character as a person can be modeled and/or decomposed into interlocking, often quantitative and yet random systems and statistics. It’s a tacit assertion in most RPGs, but the brilliancy of Disco Elysium is to 24-furcate “your” personality into modules that interact, compete, and importantly are not created equal. More than just being an engaging game system, the 24 skills, which are personified and voice-acted as inner impulses, implore you to decompose your own personality as such. Are you the person who wants a cigarette right now? Are you also the person who empathizes with the stupid little dog in the video? The verb “to be” is, as usual, deployed sloppily here, but the real point is that questions of identity can indeed be more interesting, and more importantly useful, than they were in dumb into philosophy class or in dumb Twitter thread where a child all-caps yells at you because of the geographical happenstance of your great-great-great-grandmother’s birth. I bring up The Witness again because that’s the other semi-recent game that made me see the world differently. Where The Witness’ commentary is about the visual world, problem solving, nature versus technology, and scientific discovery, Disco Elysium gets its hands dirty with society and interpersonal communication. A must-play for many gamers. And many non-gamers! Disco Elysium makes me optimistic about the future of literature in a time when it is so easy to feel that no good books will ever be written or read ever again.

In COVID isolation I began playing Metal Gear Solid V: the Phantom Pain, indeed my first earnest foray into the franchise. Having never gotten into war-based games or even first-person-shooters generally, I must admit that the gratuitous and at least somewhat realistic violence does make the stomach quiver. I was surprised to feel that. It’s a great game, though. Its interlocking systems play well together and its storytelling could never work in any non-videogame format — good. To pick some nits, Quiet’s outfit is utterly retarded and I have no idea why there is an online component at all (I am several years late, though). A few frustrating moments due to checkpoint mechanic, too. Highlights: C4 on anything; the unbelievable smoothness of the animation; the cassette tapes instead of codecs. I love some of the details of the control system that make the action extra visceral: hitting R2 repeatedly instead of just once to choke out a dude in your clutches; the fact that Snake’s body moves when it would have to to achieve certain neck-craning camera angles; the hilarious moment of Fulton-ing a waking-up solider back to Mother Base at a jillion miles an hour.

Sluggish Morss: Pattern Circus disappointed me slightly if only because I loved Dujanah so much. Never really “got” this new one but enjoyed my time nonetheless. More than any other developer, Jack King-Spooner makes me want to get up and make games. Living proof that someone with non-generic tastes in music, art, and writing can step up to the plate.

~ ~ ~

The one morsel of mercy 2021 leaked onto us was the return of Survivor, the only good TV show ever. Season 41 had like two-and-a-half bad episodes but several good ones and a couple great ones. My #1 “rootin’ for you, baby” character fell victim to a questionable strategic decision but I really dig the winner and predict her game to be seen as a gold standard for a certain type of gameplay that thankfully opposes some of Jeff’s seemingly unending appetite for Big Moves™. Someday I will write my own treatise on Survivor. I have to. Mario J. Lanza is the best Survivor writer ever if you have seen the sho, but I think that with a chunky handful of hours I could produce an essay that would do the job of enticing someone to take the plunge into Mark Burnett’s sacred realm. [For what it’s worth, I put M.B. as the great genius of the early 21st century — even greater than Trump (who Burnett sharpened, if not created as the figure he was during the lead-up to his election).]

Hopefully the producers are at least beginning to learn their lessons about all the twists and advantages. The episodes focusing on those flopped, the more “classical” episodes soared. Sadly, the most interesting strategic twist, the Shot in the Dark, had about as much impact as a fart in a jacuzzi. They probably never would have even mentioned it if Sydney (incredible character — a travesty she wasn’t on the jury) hadn’t played hers. Whatever. Glad to know they’re leaning towards non-returnee casts as well, which are ultimately better, as fun as it can be to root for old favorites. Best moments of the season: Xander executing (what was obviously) Tiffany’s and Evvie’s idol plan; Shan’s arc; honestly JD shouting “money!” as he fumbles the bag as hard as anyone ever has; Naseer “un-throwing” the challenge; and honorable mention: “Baruch HaShem we’re eating.”

~ ~ ~

Eh, here’s to a MUCH better 2022. Bar’s too low to wish for anything less. Keep swinging out there. Here’s my link to music you’ve definitely never heard.